The Great Hall of the Folger Shakespeare Library used to be a dark space, its tall windows covered to prevent damage to the rare books and documents on display there. The Hall, and the adjacent Folger Theatre, were the only parts of the building to which the public had access, and neither was terribly inviting. Crowds thronged the small, cramped hallway leading to the theater during intermission and despite a regular schedule of first-rate exhibitions, the Great Hall was often empty, and funereal.

World

Perspective | The world’s largest Shakespeare collection finally has the home it deserves

Today, the light floods in, illuminating the Great Hall’s intricate wood paneling, the ornate plaster ceiling and the two curious seals — an eagle for the United States and the coat of arms of Elizabeth I — above the doors. After a more than four-year renovation and expansion, the Folger now has designated exhibition space with carefully regulated lighting underground, and the Great Hall will be used for social space, events and a cafe. When the Folger begins welcoming visitors once again on Friday, it will be a building transformed, better able to serve its core mission of scholarship, but with greatly expanded public access.

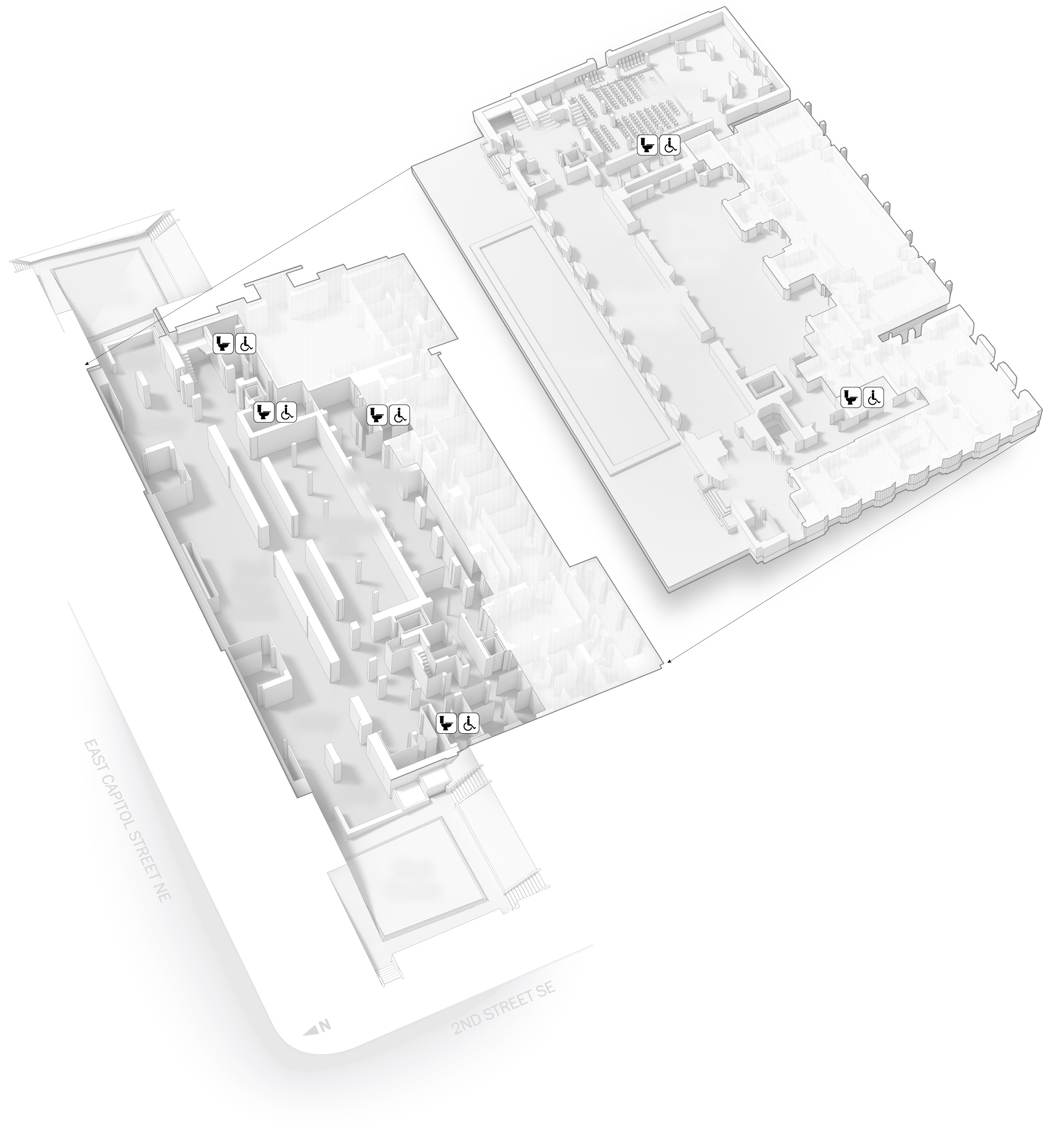

Led by Kieran Timberlake, the same architecture firm that designed the U.S. Embassy in London, the $80.5 million project adds 12,000 square feet of public space, with an exhibition gallery built around the symbolic centerpiece of the Folger’s collection, the 82 First Folios of Shakespeare, the 1623 publication that is one of the most sought-after and important books in the history of publishing. These are a relic of the library’s past, when its founders sought to prove their bibliographic zeal and devotion to the Bard by buying up as many copies as they could of the early edition of his plays. Now, for the first time, they will be on public display.

The change to the building is pervasive, both subtle and transformational. The more welcoming entrances and amenities provide a public analogue to the Folger’s behind-the-scenes importance as an international cultural institution, obvious to those who know and love Shakespeare, but not always obvious to ordinary visitors to Washington, or Capitol Hill.

The Folger has the largest collection of Shakespeare material in the world and the largest collection of First Folios, and it is a center for the study of the early modern world — the period from the 16th to the beginning of the 19th century that gave us not just Shakespeare, but also our essential ideas about race, identity, capitalism, public life and entertainment. By opening itself more forthrightly to a wider audience, the library is doing something that Henry Clay Folger could probably never have imagined would be necessary: assert the importance of Shakespeare to public life, from scholars to laymen, passersby and politicians.

Designed by architect Paul Philippe Cret to house the Shakespeareana collection gathered by Folger and his wife, Emily Jordan Folger, the library opened in 1932, three years before the Supreme Court moved into its building located kitty-corner to it. Its architecture used political and religious motifs to assert Shakespeare’s quasi-sacred status. In the main reading room, approached through a low-ceilinged chamber like the narthex of a cathedral, a giant stained glass window faced west.

Symbolically, the faux-Tudor Great Hall, with its high ceilings, tall windows, dark wood paneling and the two seals representing the United States and Elizabethan England, represents not just the presumption of its American creator, Henry Folger, to be a steward of Anglo-Saxon culture, but the hope that Shakespeare, and the Folger Shakespeare Library, would weave the nation’s political, civic and cultural life into a harmonious and erudite unity.

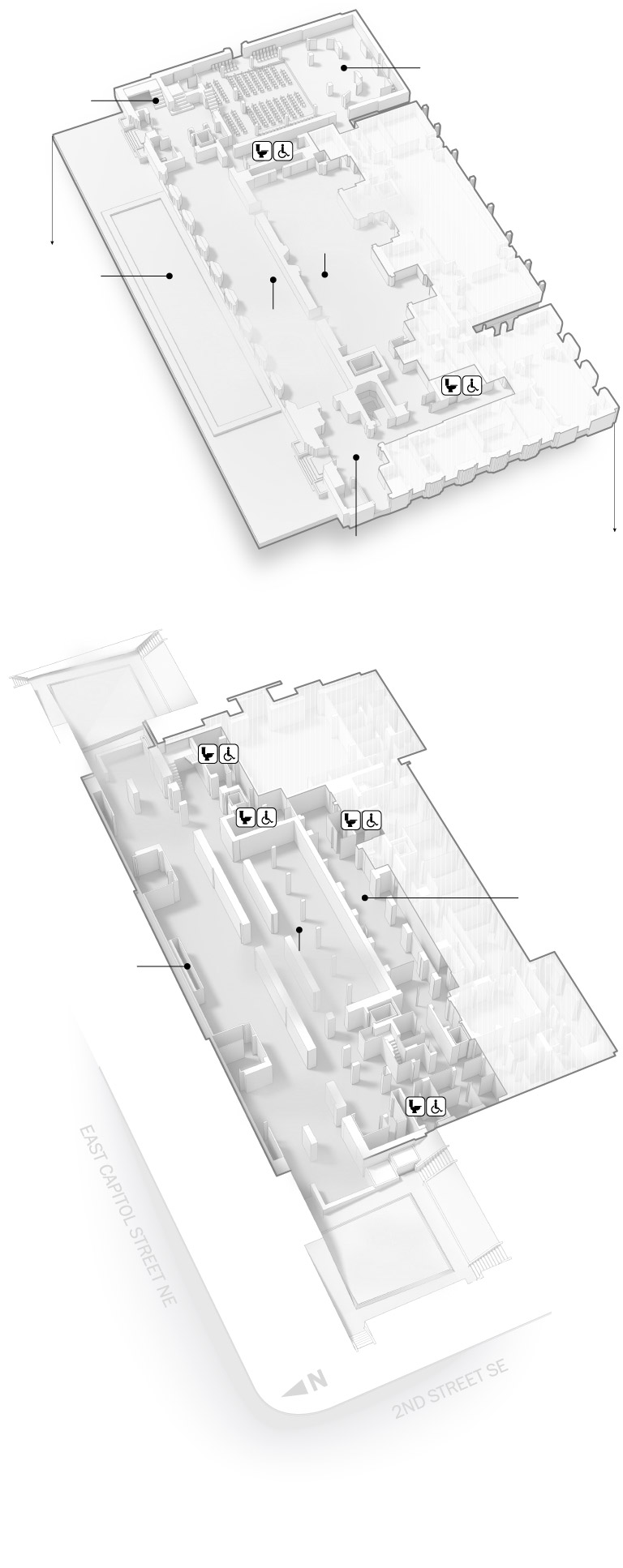

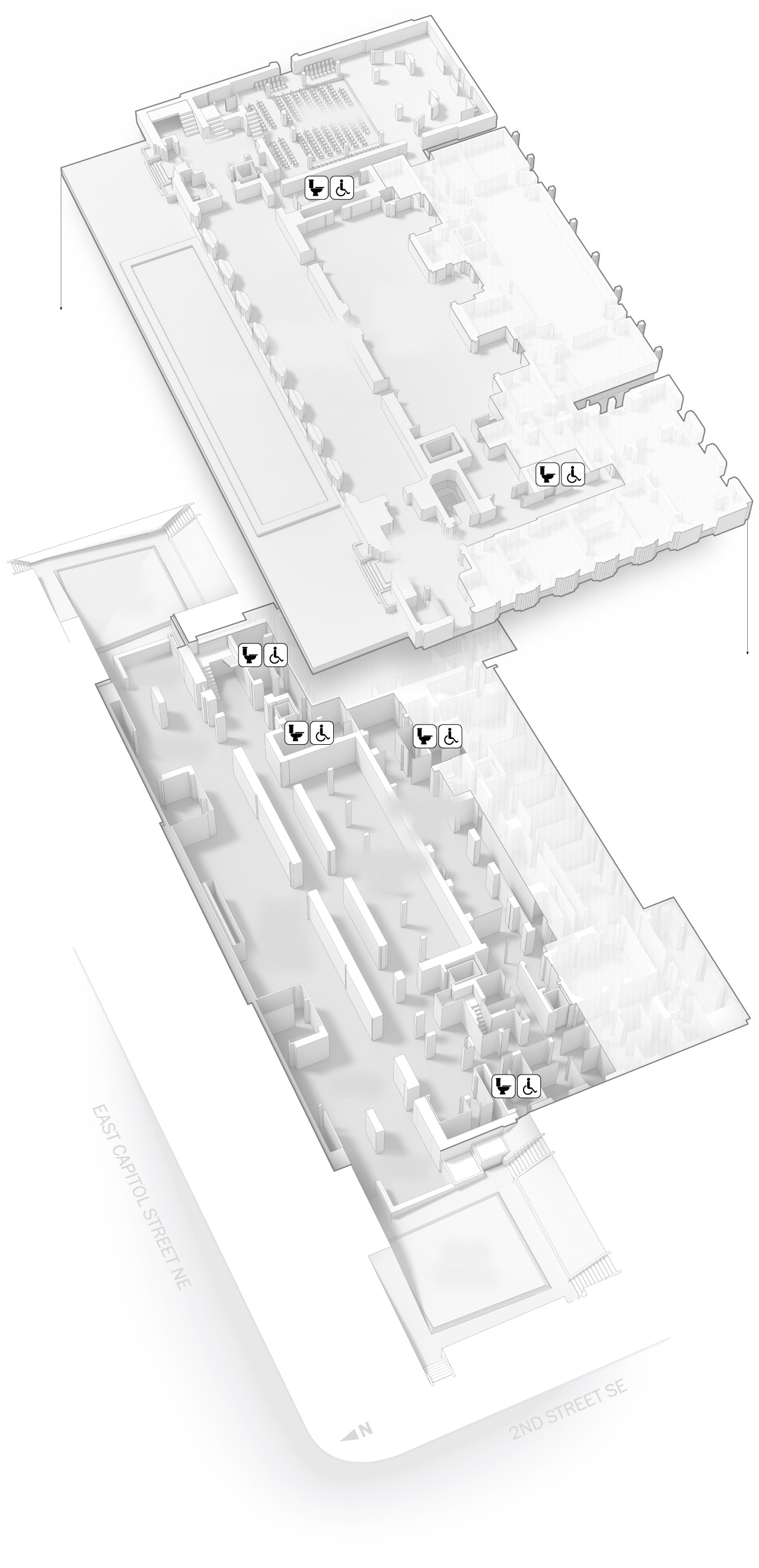

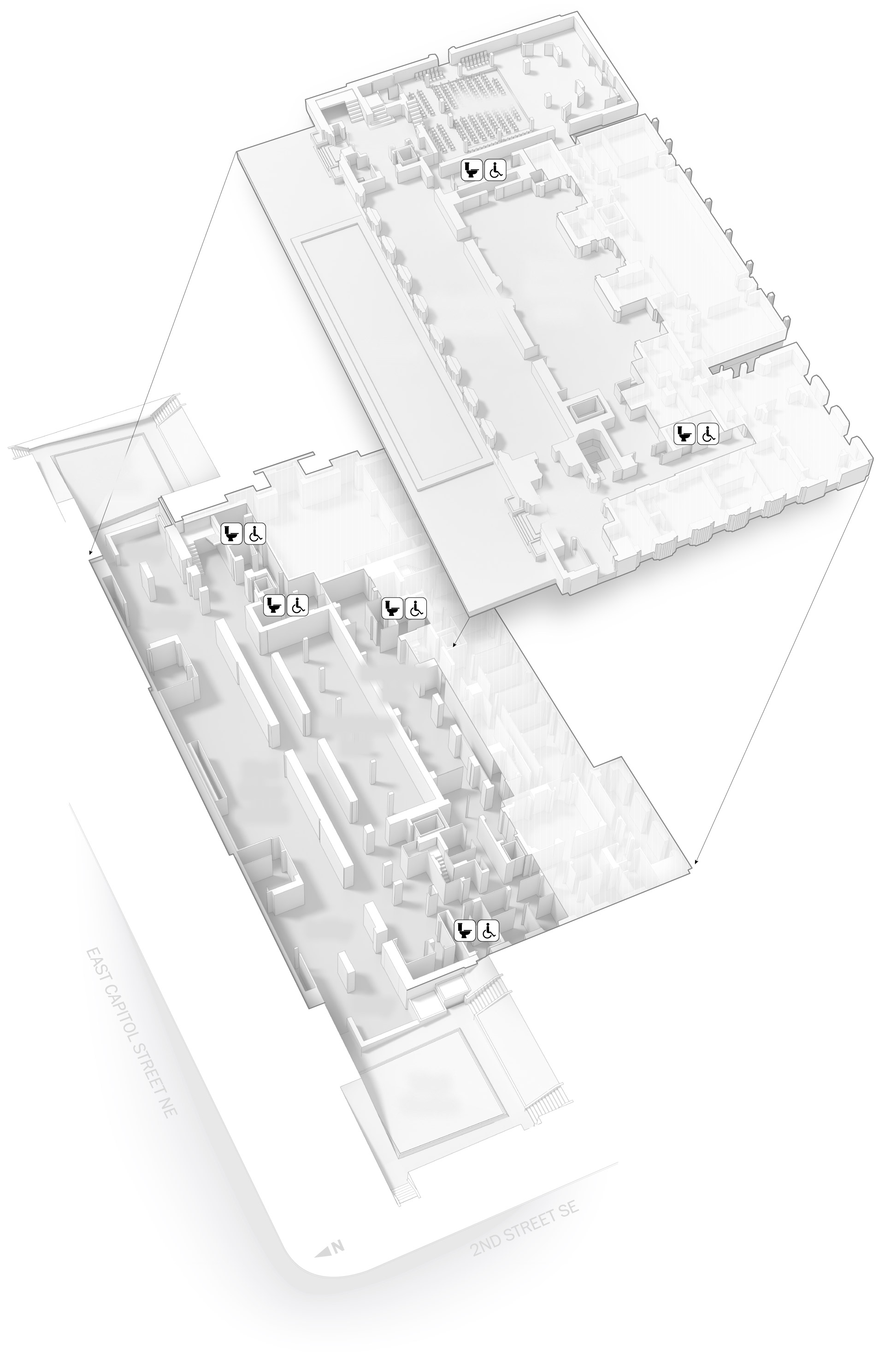

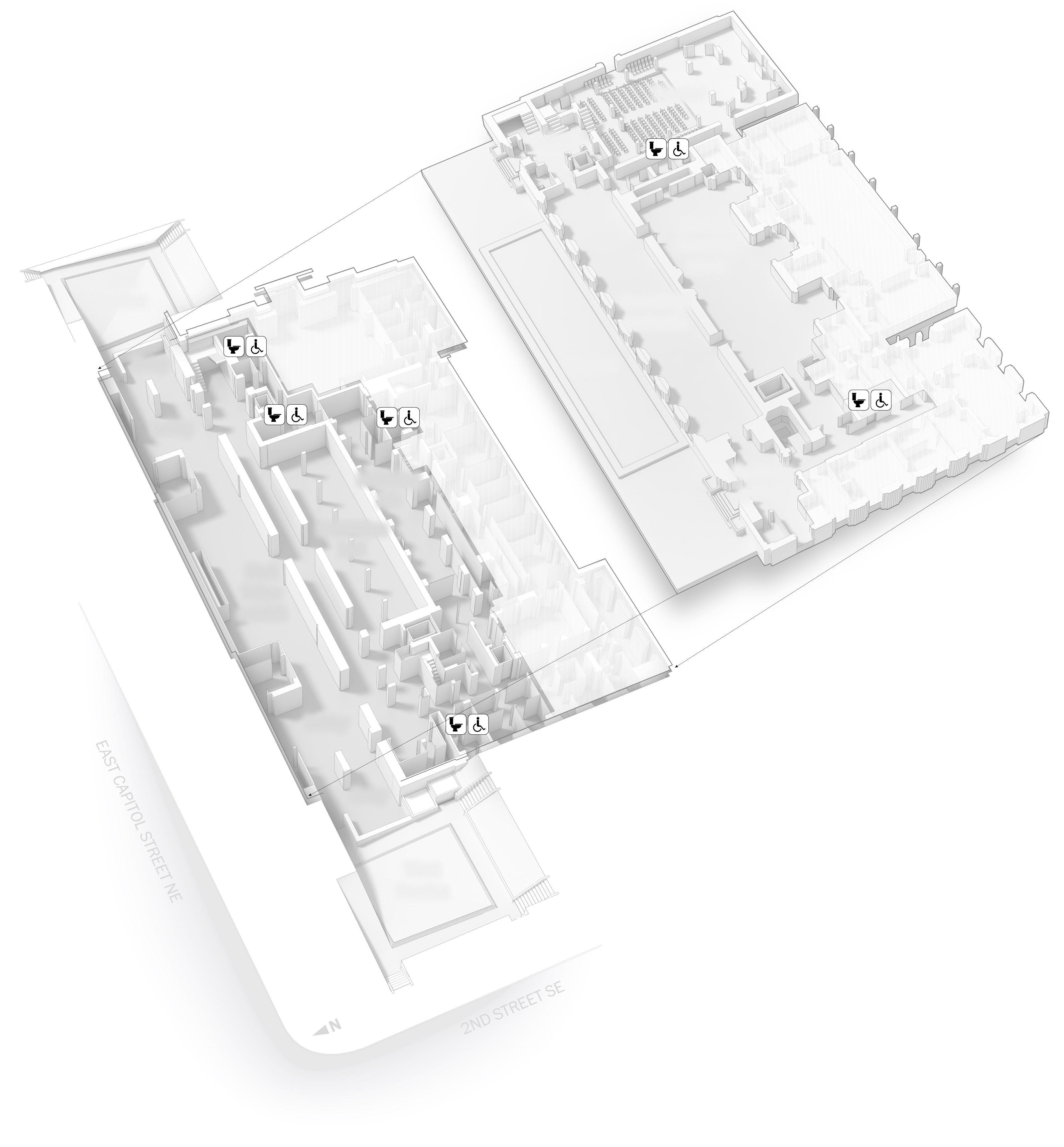

Like other buildings nearby, including the Capitol, the Folger was landlocked; to expand, the architects had to go underground. That meant a big dig, and an opportunity to attend to issues like accessibility and things often invisible to the public: HVAC, fire suppression, mechanical systems and security. The entire collection — more than four miles of books and other materials — had to be moved off-site, and for more than a year the building’s facade was suspended on steel framing while the new spaces were being constructed.

“The investment was massive,” says Folger Director Michael Witmore. “But it feels good now that the collections are almost back in the building to say, you know, while the patient was open on the table, we did everything we could do.”

Offices and

mechanical

space

Sources: Folger Shakespeare Library; KieranTimberlake

AARON STECKELBERG/THE WASHINGTON POST

Offices and

mechanical

space

Sources: Folger Shakespeare Library; KieranTimberlake

AARON STECKELBERG/THE WASHINGTON POST

Offices and

mechanical

space

Sources: Folger Shakespeare Library; KieranTimberlake

AARON STECKELBERG/THE WASHINGTON POST

Offices and

mechanical

space

Sources: Folger Shakespeare Library; KieranTimberlake

AARON STECKELBERG/THE WASHINGTON POST

Offices and

mechanical

space

Sources: Folger Shakespeare Library; KieranTimberlake

AARON STECKELBERG/THE WASHINGTON POST

Offices and

mechanical

space

Sources: Folger Shakespeare Library; KieranTimberlake

AARON STECKELBERG/THE WASHINGTON POST

The most significant change is the new underground gallery space, approached by gentle ramps through two new gardens (designed by the Olin Studio) at the east and west ends of the building.

“People thought we were a bank, and we were closed,” says Witmore, standing at the top of the ramp that leads to the new west entrance, with Cret’s oblong building, both a memorial and a functioning library, in front of him. Cret’s design, a stripped-down classicism that feels lean, elegant, formal and austere — like a bank — hasn’t been changed in any essentials. It still sits on a plinth, like a temple, with its distinctive bas-relief depictions of famous plays arrayed at the ideal level for viewing from your car window.

But visitors are now invited to enter through an underground exhibition hall that includes a rotating display of the Folger’s collection, including the 82 First Folios arrayed on shelves like treasures in a vault, or corpses in a morgue. They rest under dim light with an interactive label system that highlights their significance — the most expensive, the latest acquired, copies once owned by women — including the Folger’s own idiosyncratic system for ordering them by importance. For the opening exhibition, Folio No. 1 is on view separately, open to the page that made it, for Henry Folger, “the most precious book in the world,” a handwritten inscription from the London publisher, William Jaggard, that includes the all-important publication date, 1623.

The exhibition positions Shakespeare in ways that would probably be seen as bizarre or foreign by Folger, an oil baron who fell in love with the poet and playwright as an undergraduate at Amherst College, and who used his fortune to collect a vast library of rare books, at a rate of some six volumes a day for more than 40 years. A portrait of Ira Aldridge, an African American actor driven by racism at home to make his career in Europe, is seen near the Folger’s invaluable 1579 “sieve” portrait of Elizabeth, by George Gower, depicting the queen with a symbol of her supposed virginal purity. Aldridge was the first Black actor to play Othello, after centuries of White actors using blackface. Nearby, a mirror sculpture by the Black artist Fred Wilson recalls his 2003 installation at the Venice Biennale, which focused on “Othello,” and invites visitors to see themselves and Gower’s portrait of Elizabeth, in a curious dual reflection.

“It’s about past and present,” says Greg Prickman, the Folger’s director of collections. “It’s different time periods, contemporary, early modern, coming together.” Henry Folger would probably have said Shakespeare is timeless, while the Folger now makes a conscious effort to connect past and present. The old oil baron would probably have assumed that the whole world thought as he did, that Shakespeare was the fount and origin of most of Anglo-Saxon culture. The new Folger exhibition expands the idea of culture to include the wider transatlantic world, connected not just by language or literature, but also by routes of trade that included the traffic of enslaved people. Shakespeare, for Folger, was a gentleman’s hobby; the Folger assumes interest in his work transcends class or identity.

So, after introducing Aldridge the exhibition takes up the difficult question of race and Shakespeare, including the role of Black writers, artists and actors in the centuries-long processing and rethinking of Shakespeare’s drama. The use of blackface by White actors, the role of Black theater troupes in reinterpreting Shakespeare, and famous productions like the 1936 “Voodoo” Macbeth set in Haiti and directed by Orson Welles with an all-Black cast are broached and illustrated with books, photographs and playbills.

The exhibition provides public access to the kind of work the Folger has been doing for years, opening up early modern studies to include a vastly wider frame of topics, people and sources. The Folger hasn’t acquired a new First Folio since the last ones bought by the Folgers in 1928, but it recently added a 1689 tract against the slave trade (one of the earliest) written in French, portraits of women writers, books with inscriptions from women and, over the past 20 years, books and sources on culinary and medical topics, including recipe volumes compiled by women.

The institution has also grappled with its own history, and all of the unwanted baggage that comes with its dedication to Shakespeare, a cultural icon too often appropriated and abused as a patron saint of racialized Anglophone identity. On Dec. 29, 2020, a letter signed by “#Stopthesteal” protesters was sent to the Folger, apologizing for any inconvenience they would cause during the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection that came close to disrupting the peaceful transfer of democratic power. The Folger published the letter on its website, and scholars of race and Shakespeare have noted the close association between white nationalism and bardolatry. The Folger has also publicly detailed an ugly incident in its own history, when Howard University professor Benjamin Brawley, who was Black, asked to be included among the invitees to the annual Shakespeare Birthday Lecture. Letters from the archives make clear how this request agitated the Folger’s leadership, who worried that including Brawley might lead to the integration of the Folger’s social functions. Brawley was ultimately invited, but Howard professors were not offered open invitations to Folger events deemed social rather than academic.

“The Folger, an institution that once operated under an exclusionary model of Anglo-European inheritance must today stand for something else — something vastly more inclusive, and vastly more self-aware,” Witmore wrote in a 2022 article in the library’s magazine.

Also largely out of sight is the role played by the Folger Institute, a center for advanced research under the larger Folger umbrella. “I don’t know that there is another institution that has been so effective at shaping new generations of scholars that are interested in the early modern period,” says Kathryn James, a scholar of the period who is also the rare book librarian at the Yale Law Library. “Almost every early modern graduate student working in British studies will apply to be a dissertation fellow there.” Those fellowships put students in contact with academic experts and include hands-on research with historic materials and the study of paleography (the deciphering of writing systems) and bibliography (the details of printing, dating, editing and classifying of books). The Folger is also a leader in the conservation of historic materials.

It’s particularly difficult to reinvent a cultural organization whose core mission is built around research and scholarship, activities that are solitary, labor-intensive, intellectual and detail oriented. The public sees only the secondary or tertiary fruits of this work, when it is processed into narratives aimed at a lay audience. Even the Folger’s collection of First Folios, which now serves as a kind of secular shrine at the heart of the new space, is valuable for the details of their marginalia, inscriptions and chains of ownership, facts that must seem esoteric to most general readers of Shakespeare.

The new building, however, allows the Folger to add front-of-house space while leaving all of its back-of-house scholarly apparatus in place, functioning as it ever has.

“There’s a history of thinking of rare books and manuscripts as delicate, living things that need to be protected,” says Witmore, the Folger’s director. “We know how to protect rare books and manuscripts, but we don’t have to repel people, including members of the public, in order to engage with that.”

When Henry and Emily Folger were assembling their Shakespeare collection, most of their newly purchased books were sent into storage. When they decided to make those materials accessible in a library, they considered sites in New York and locations including Stratford-upon-Avon in England, but decided on Washington after taking a walk from Union Station to Capitol Hill in 1918. Washington, once a grubby backwater, was finally looking like an actual capital, the fruit of a monumental remaking of the city that began around the turn of the century by progressive designers associated with the City Beautiful movement. The Folgers acquired land near or adjacent to some of the city’s most important civic buildings, buying up rowhouses as they bought many of their books — anonymously — before announcing their plans in 1928.

“I finally concluded I would give it to Washington, for I am an American,” Folger said. The idea behind this was quaint, that the proximity of cultural and political institutions might invigorate both and insulate the latter from stupidity and corruption.

But vestiges of the idea survive in the humanities, now a frequent target of attack by opportunistic politicians. At the Folger, it is a commitment to both access and diligence, an open-ended invitation to the public to learn about Shakespeare and a continuing engagement with the minutiae and details of scholarship. Working hard on difficult questions, the answer to which may not be immediately forthcoming nor the value of which immediately obvious, and doing that in the shadow of the nation’s Capitol, sets an example to politicians, whether they heed it or not.

Or as James, of the Yale Law Library, puts it: “Enticing visitors and researchers into being interested in things that they might not have known about before — that is a politics in its own right.”

The Folger Shakespeare Library (201 E. Capitol St. SE) is open 11 a.m.-6 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday, with extended hours to 9 p.m. on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays. Free timed entry passes are recommended. www.folger.edu.