Gambling

Poacher turned gamekeeper: the gambler who turned tables on bookies and lobbies for UK tax rise

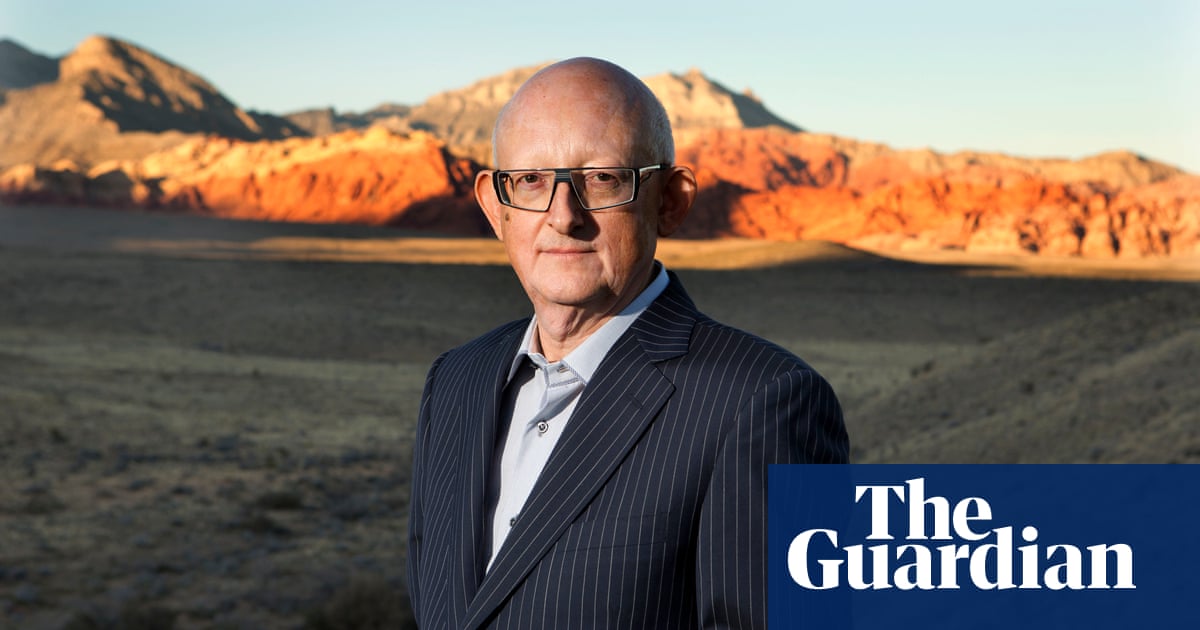

As a former professional poker player, Derek Webb is used to rising from the table holding more chips than he started with.

Vanquished opponents are left scratching their heads, wondering how they have been bested by a softly spoken, bespectacled septuagenarian with a Derby accent.

Now, the multimillionaire is going all-in on a new battle with the very industry where he cut his teeth – the gambling sector.

Webb has beaten the house before, having provided financial backing for the successful campaign to restrict £100-a-spin fixed odds betting terminals (FOBTs).

This time, the stakes are high, up to £3bn a year in the form of the duty that the gambling sector pays to the exchequer.

As the Guardian reveals today, Treasury officials are considering proposals to double taxes levied on parts of the sector, as the chancellor, Rachel Reeves, aims to pull every lever possible to raise funds in her upcoming budget.

The industry, which wins £11bn from British punters every year, is pushing back, warning of the twin spectres of the hidden market and economic damage to a sector that claims to support 110,000 jobs.

Historically, gambling is an industry that has wielded influence with Labour, thanks in part to donations worth more than £400,000 since 2020, some of it to Reeves’ own office.

But Webb has blown that figure out of the water, quietly becoming Labour’s fifth-largest individual donor since the beginning of 2023 by channelling £1.3m of his money into the party over the period.

Much of Webb’s fortune has come courtesy of casino companies that dared to mess with the intellectual property rights to Three Card Poker. Webb devised the game, sold the rights for $25m and has since made significantly more as a litigant, defending his position and supporting litigation by others.

He also provides funds to the Social Market Foundation, one of two influential thinktanks – along with the IPPR – now pushing the Treasury to raises taxes on the sector by £900m and up to £3bn respectively.

“I’m motivated to try to change the gambling regulatory system,” said Webb, who is also funding campaigns to restrict gambling advertising and tighten up regulation of the sector, through organisations such as Gambling With Lives and the Campaign for Fairer Gambling.

“It would be a dereliction of duty if they [the Treasury] don’t do something, but that’s not up to me.”

Some in the gambling sector have suggested that Webb may be motivated by ties to the land-based casino sector, which in theory could benefit if competitors for the gambling pound, such as bookmakers and online casinos, have their wings clipped.

Webb dismisses this, insisting that he no longer has any financial interest in casinos and was, in any case, never likely to have benefited significantly from pouring his own money into politics and campaigning. He will also oppose any liberalisation of laws on the land-based sector, he said.

“I’m a believer in socioeconomic justice,” he said, adding that the Conservatives’ failure to get last year’s white paper on gambling reform right, in his eyes, is behind his donations to Labour. He has also given £250,000 to the Liberal Democrats, who also want to raise taxes on online gambling, to fund better pay for social care workers.

Increasing dismay at the predatory tactics of British gambling operators, he says, lay behind his decision to pour some of that cash into campaigning, first to curb £100-a-spin FOBTs and now for further regulatory reform and tax rises.

after newsletter promotion

The SMF, which has received up to £40,000 from Webb in the past two years for which funding information is available, is expected to highlight that British-owned gambling firms operate profitably in other countries where they pay higher rates, such as the US and the Netherlands.

Its argument to the Treasury is that remote gaming duty, levied on online gambling companies, could be doubled to 42%, raising an extra £900m, with no ill effects.

Privately, some of those who have been pressing Treasury officials to line up behind reform of betting duties think that they may be winning the argument.

“It’s definitely on the map,” said one. “There’s no obvious pushback to it.”

But the gambling industry will be no pushover.

The chair of its lobbying group, the Betting and Gaming Council, is Michael Dugher, a former Labour MP and spokesperson for Gordon Brown, whose contacts book, if not his rhetoric, has served the industry well.

His rather slicker successor as the lobby group’s chief executive, Grainne Hurst, is a former executive at gambling group Entain, but knows her way around Westminster too.

She previously worked for Philip Davies, the notoriously gambling-friendly Conservative MP who infamously bet, successfully, that he would lose his seat at the last election.

Alongside the industry’s donations to Labour sit a host of freebies, such as sports and gig tickets, with recipients including Reeves and two other ministers with a voice on gambling policy, the health secretary, Wes Streeting, and the business secretary, Jonathan Reynolds.

The chips have been placed but, with the budget just weeks away, it is far from clear which player has the strongest hand.