World

Team Argo’s Yokohama Record | Sailing World

Chad Corning

It’s 2 a.m., and I’m not having much luck sleeping. The wailing of Argo’s T-foil rudders cuts right through my earplugs, and I’ve become a bit too familiar with how the underside of the deck feels as the boat falls off wave after wave. Suddenly, it’s quiet as the central hull lifts entirely out of the water. I know what’s next—a violent deceleration as the boat touches down and noses into the wave in front. I do a reflexive deep knee bend as the boat stops, and my body keeps going. Without a word, the off watch piles out and heads on deck. It’s clearly time for the second reef. It’s a battle scene on deck as off-axis waves merge and explode around us; the rain stings like needles. OK, Reef 2 in, staysail furled; let’s hope that this is the worst of it.

Attempting the Honolulu-to-Yokohama record was a neat solution to a logistics problem. After the 2023 Transpacific Yacht Race, with our next race half a world away in the Canary Islands, we decided that the path of least resistance was to keep following the trade winds west and catch a ship in Japan. Memories of the 10-day upwind trip back to California from Hawaii in 2019 reinforced this thinking. We could also focus the voyage around chasing one of Steve Fossett’s oldest speed records along this route, set on his ORMA 60, Lakota, in 1995.

This was our fourth attempt to break one of the World Sailing Speed Record Council’s records. Previously, we had a COVID-busting trip across the Atlantic to set a new Bermuda-to-Plymouth record in 2021, and a stormy but fast trip to set a new mark from Antigua to Newport in 2022. Our sailing master, Brian Thompson, joked that he was racing himself because he had skippered the MOD 70 Phaedo for both records. Thompson was also aboard Lakota when they beat the Honolulu-to-Yokohama record in 1995, though he would miss this trip with us. We also had one miss when we stood by for an attempt on the extremely fast Newport-to-Bermuda record in 2022, but the unicorn weather that would allow it (pre-frontal westerly, calm winds before) never came to pass.

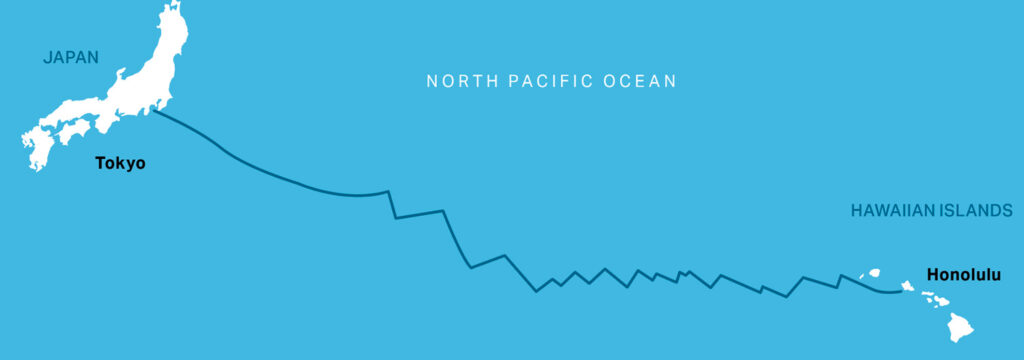

Once through the hoops of registering with the WSSRC, coordinating with starting and finishing commissioners, and wiring in the black-box tracker, we were ready to “stand by” for a good weather window for the 3,350-mile course. Frustratingly, once we assembled in Hawaii for our first attempt, one low after another formed in the South Pacific and spun into typhoons that menaced the Japanese coast. After waiting a week, we had to call time and regroup for another try a bit later, knowing that risk was increasing as we got further into typhoon season. After a few weeks, a good window presented itself, and we went to “code green,” with the team piling onto airplanes worldwide and heading to Hawaii. Argo regulars Westy Barlow, myself, and Pete Cumming were aboard, along with Paul Larsen (the world’s fastest person aboard Sailrocket), Paul Allen, and James Dodd. Most arrived on the day of departure; we would eventually cross the start line off Diamond Head just after dark, at 8:30 p.m. on August 20.

We stormed out of the barn, knocking 500 miles off the trip in the first 24 hours in strong easterly winds, which were great for morale. But the Pacific soon lived up to its name when we sailed up to a 1,600-nautical-mile oblong area of high pressure parked directly on the rhumb line—time to head south, way south, to stay in the trades. The jibe fest began. Sailing on starboard brought us up to the light winds on the southern edge of the high, and jibing to the south brought us into more wind but yielded very little VMG. We jibed endlessly and on the slightest shifts, anxious to spend as little time sailing to the south as possible. The jibing and our southern routing would add more than 1,200 miles to the trip, which didn’t necessarily help with morale.

A Groundhog Day vibe overcame the boat as we bounced along the southern edge of the high for four days. Nothing changed. Air temp was 92 degrees F, with water temp at 87, a few high clouds, fierce sun, a 1-meter swell, and true-wind stuck on 15 knots. The distance to go seemed to tick down at a glacial pace. Days blended.

The chart plotter, usually alive with AIS targets and land, was blank; even depth contours were gone, with the bottom miles away. We had to pan way out to pick up even the smallest (uninhabited) atoll. We didn’t see or pick up a ship on AIS until the last 100 miles; the Pacific was empty. Empty but pristine, with no trash and no debris, just miles of orderly swells going on seemingly forever. Wildlife was limited to flying fish and the frigate birds that wanted to eat them—both were ubiquitous the entire trip.

Though it was pretty outside the window, living conditions were harsh on board in the unrelenting heat. Down below was an oven during the day, easily exceeding 100 degrees F, making sleep impossible. We withered away with little appetite and pined for the nights, which were just cool enough to sleep and be comfortable on deck. The night sky’s clarity was incredible, with shooting stars and the pearl necklace of Starlink satellites occasionally lighting up, making the whole scene a moving work of art.

The idyllic conditions ended as we intersected with a robust low-pressure system toward the end of the trip. This was meant to be good news because it would boost the notoriously light winds near the Japanese coast, which had slowed Lakota dramatically in 1995. It became more of a mixed blessing as the low deepened and showed signs of rotation. Eventually, it would develop into Typhoon Damrey, with sustained winds of 75 knots and gusts to 95. Very warm water made for rapid development and intensification—and the rapid development of concern on board.

The storm lay about 175 miles northwest of us, leaving its messy tail for us to cross behind. Our first move was to slow the boat to let the storm advance away from us. We then tried to cross its path by jibing to the west to get across the strong winds and sea state as quickly as possible. It was too windy and rough when we initially gave it a go, leading us to bail and sail in the more-benign conditions near the high for another 100 miles before trying again. The second attempt stuck, but we had a very unpleasant 24 hours of it, with winds far over forecast (which occurs frustratingly often in these scenarios) and up to 40 knots. The sea state was disorganized, with the storm waves on the beam and the prevailing swell coming from behind. We were still sailing downwind and trying hard to slow down. We kept in reasonable control most of the time. The sea state was our biggest issue: The storm waves and swell would merge and then break; at the bottom of many of these, the boat would almost completely disappear beneath us. A unique head space was required—a Bruce Lee “total concentration” mindset—to helm the boat in these conditions. An hourlong stint at the helm seemed like an eternity. The MODs are famously tough boats; ours passed this stern test with flying colors. The sailors had a more challenging time; the stress and physicality of the sailing drained relatively low energy reserves to near zero.

After one last line of squalls, we finally broke back into clear weather and started our long port jibe into the finish. Though we had cursed the sun through the beginning of the trip, it was most welcome to see it again and to begin drying out. Marine life increased, we saw ships, and our reentry into civilization began. One last challenge was negotiating the Kuroshiro Current, similar to the Gulf Stream. As we approached the coast, this and the shoaling water produced spectacularly sized waves around 6 meters high. These were benign because they were well-spaced, but being in the trough gave us one last sensation of the indifferent power of the ocean.

A smudge on the horizon soon revealed itself to be Mount Fuji, with the rest of the striking Japanese coast following. We had one last satisfying rip through Yokohama Bay and streaked by Jogashima Lighthouse, stopping the clock at 7 days, 18 hours, 25 minutes. After finishing, we gave a quiet chapeau to Steve Fossett, a pioneer in our sport who circled the world in search of new records and adventure. He was a noble adversary, and it was a true honor to “race” him on this beautiful and challenging course.