When Sultan Ahmed al-Mansur ascended the throne of the Saadi dynasty in 1578, he set out to showcase the newfound power and prosperity gained from the Portuguese defeat, a victory that brought both prestige and wealth.

Shortly after assuming the throne, he launched the ambitious construction of the El Badi Palace in Marrakech, a symbol of a new era. He also formed alliances with Western powers, notably with the English, through a series of diplomatic missions to London.

Above all, he sought to distance himself from the close ties his late brother, Sultan Marwan Abd al-Malik—who died in the battle against the Portuguese at Ksar el-Kebir—had established with the Ottomans.

Fashion as a political statement

This break from the Ottomans went beyond politics; it extended to fashion. Ahmed al-Mansur understood the power of fashion as a historical and political statement. Unlike his brother, who had spent 17 years in Ottoman-controlled territories and adopted Ottoman attire at court, al-Mansur sought to revive traditional Moroccan dress.

According to Moroccan historian Nabil Mouline in his research paper «Le Califat imaginaire d’Ahmad al-Mansûr: Pouvoir et diplomatie au Maroc au XVIe siècle», Abd al-Malik’s exposure to Ottoman culture had led him to abandon the longstanding Moroccan dress customs. Mouline notes, «This prince, who had lived most of his life in Ottoman lands, decided to adopt their dress code and even imposed it on his subjects».

By dressing in luxurious Ottoman clothing and discarding the traditional white attire of former Saadi sultans, Abd al-Malik was not only abandoning local tradition but, in a way, acknowledging Ottoman influence.

However, when Ahmed al-Mansur came to power, he deliberately broke with this tradition, restoring the «local tradition of dressing» at the Saadi court. Mouline, drawing on reports from the first Spanish embassy to Morocco under al-Mansur in 1579, writes that al-Mansur «wore white clothes in the Moroccan style and had a turban on his head». This return to traditional dress was a powerful political statement, signaling that al-Mansur «did not recognize Ottoman sovereignty».

Mouline further explains, «Within months of his accession, the Sultan restored the white color as the emblem of the Western Caliphate (Saadi state). The term ‘Moroccan’ to describe the Sultan’s dress illustrates the contrast with the ‘Turkish’ style adopted by his predecessor». By doing so, al-Mansur was affirming the «independence and sovereignty» of the Saadi dynasty, a political stance the sultan termed «the Western Islamic caliphate».

Mansouria, innovating Moroccan fashion

Al-Mansur didn’t simply revive tradition; he also introduced new styles to Saadi fashion. A description by Spanish agent Jorge de Henin in the early 17th century offers insight into the attire of Saadi rulers at the time. According to Mouline, de Henin describes the sultan’s son Abu Faris as wearing «wide trousers cinched at the waist by a silk belt embroidered along the sides, a shirt with narrow sleeves and buttons at the wrists, and over it a long, wide-sleeved garment known as a mansuriya (Mansouria)».

This garment, the Mansouria, was a new addition attributed to Sultan Ahmed al-Mansur. Made of fine muslin and specifically designed for him, the mansouria later became known by his name. Historian Ahmad al-Maqqari al-Tilmisani, a contemporary of Ahmed al-Mansur, refers to this garment in Nafh at-Tib, a historical compendium of Al-Andalus and Morocco, describing the Mansouria as a «type of clothing known in Morocco», crafted for the sultan and later named after him.

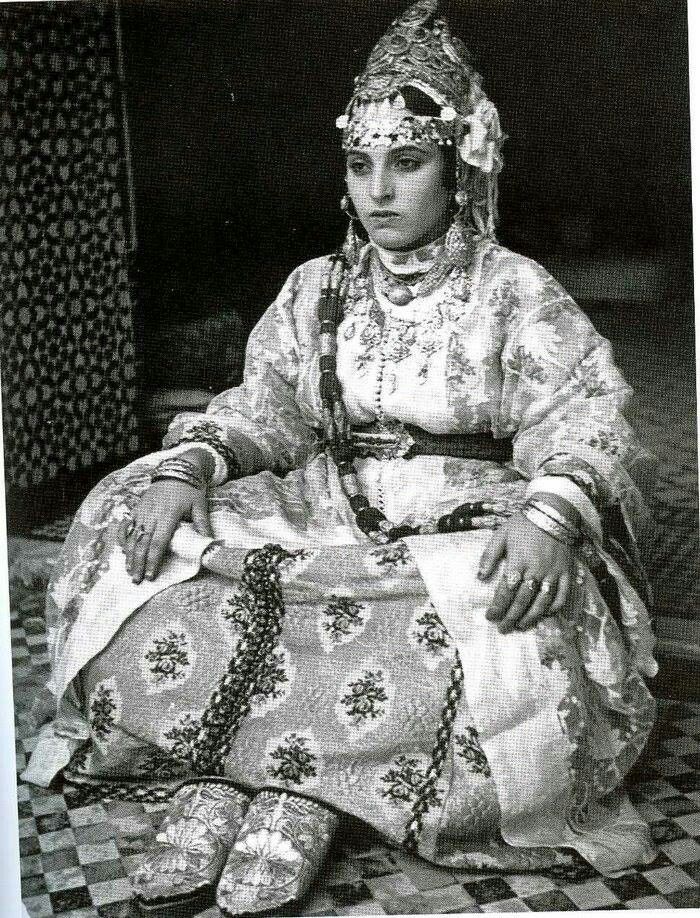

According to sources on traditional Moroccan clothing, the Mansouria was typically worn over the caftan. Originally worn by both men and women, it eventually became a statement piece for women, especially those in cities.

The book Costumes of Morocco notes that the Mansouria served as the izar—an outer garment—especially popular among wealthy urban women who wore it instead of the more common izar. «The izar is longer and made of muslin, with wide sleeves, resembling the dfina of the towns, also known as farajtya or mansuriya», reads the book.

It adds, «All these light cottons and decorated muslins are imported. They are bought in nearby town souks and bring urban luxury to the countryside, gradually replacing simple cottons, now reserved for daily wear».

The Mansouria, later called farajiya, was worn over the caftan, typically made of muslin to reveal the elegance of the garment underneath. Along with other traditional Moroccan attire such as the gandoura, takchita, and djellaba, this garment has endured through the ages, illustrating the ways in which politics can shape and preserve fashion.