Travel

The Risks of Self-Fulfilling Travel Forecasts

The U.S. Department of Transportation just released its latest Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) Forecast which predicts that vehicle travel will grow between 0.4 percent and 0.8 percent annually between now and 2050, depending on economic growth rates. This is bad planning.

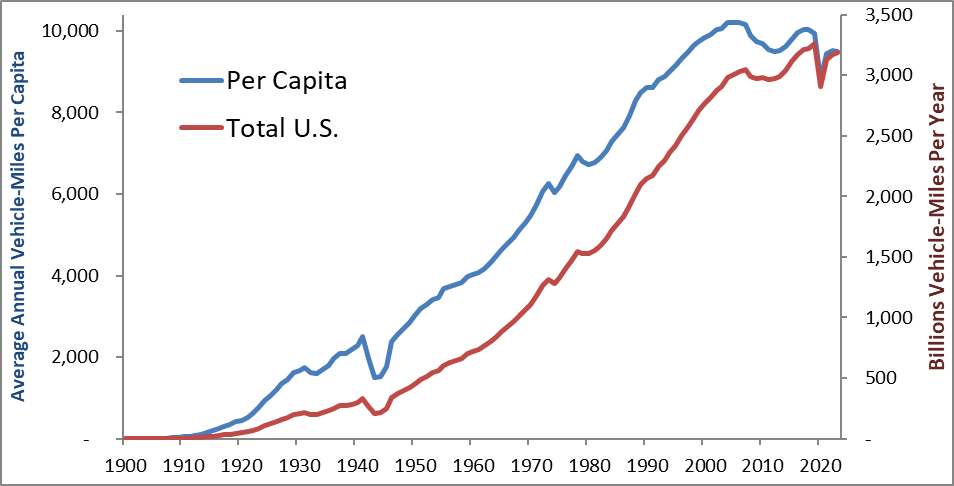

These forecasts simply extrapolate past trends; they assume that if vehicle travel grew at a certain rate in the past it will continue at that rate into the future, ignoring underlying factors that may affect travel activity. In particular, the DOT forecast assumes that vehicle travel always increases with economic productivity although recent trends indicate decoupling, and it assumes that per capita vehicle travel will grow although it actually peaked in 2004, as illustrated below. Many current trends — aging population, rising travel costs, increased urbanization, new technologies (telework and e-bikes), increasing health and environmental concerns, plus changing consumer preferences — are likely to suppress future vehicle travel growth if we let them; the DOT forecast ignores that possibility.

US Motor Vehicle Travel Trends (FHWA 2024)

Of course, future travel trends are contingent on planning decisions. Although few motorists want to forego automobile travel altogether, surveys indicate that many would prefer to drive less and rely more on walking, bicycling, and public transport, provided those options are convenient, comfortable, and affordable. Many current policies favor driving over other modes, creating automobile-dependent communities. For example, zoning codes force property owners to subsidize costly parking, transportation funding favors faster modes over slower but more affordable, healthier, and resource-efficient modes, and development policies favor sprawl over compact infill. Reforming these policies would improve non-auto transportation options, reducing vehicle travel.

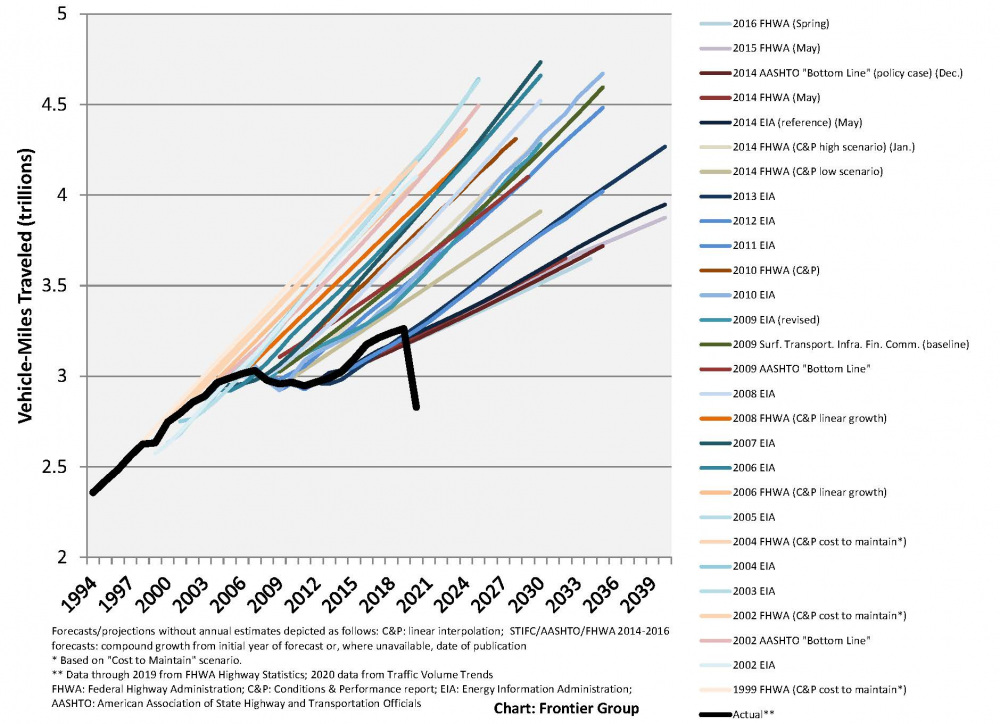

In fact, previous travel forecasts have proven to be wildly inaccurate, as described in the State Smart Transportation Initiative’s research, States Overestimating VMT Growth, as illustrated in the following graph:

The problem is that vehicle travel projections tend to be self-fulfilling. Transportation agencies treat such predictions as inflexible futures that must be accommodated rather than possibilities that are influenced by their decisions. If practitioners predict that vehicle travel will increase by a certain amount they feel obliged to expand roadway capacity by that amount, a process called “predict and provide planning.”

My previous column, Transportation Agencies: Improve Your Models or Hire More Lawyers, highlights the related problems of exaggerated vehicle travel forecasts, exaggerated predictions of future congestion problems, and exaggerated predictions of highway expansion benefits, resulting in far larger roadways than economically justified, and underinvestment in alternatives.

A better approach, called “decide and provide planning,” means that policy makers set targets for agencies to achieve. For example, a community might have goals to reduce traffic congestion, crashes and emissions, improve public fitness and health, and create more affordable and livable neighborhoods. Individual planning decisions related to parking regulations, transportation infrastructure investments, roadway design and development policies are then aligned to support those goals.

Rather than simply extrapolating past trends, this approach recognizes changing user demands, emerging planning goals, capacity limits, and an expanded range of potential solutions. If a community’s population is predicted to grow 10% during the next decade, decide and provide planning finds ways to reduce per capita vehicle trip generation by 10% during that period, so traffic problems don’t increase, or a larger reduction if the goal is to reduce traffic problems below current levels.

Many jurisdictions are starting to apply this approach, as described in my column, When it Comes to Vehicle Travel, Less is More. For example, California has targets to reduce per capita light-duty VMT 25 percent by 2030 and 30 percent by 2045, and has developed guidance policies and analysis tools to support those goals. Washington State has targets to reduce vehicle travel 30% by 2035 and 50 percent by 2050, and has commute trip reduction programs that encourage employees to shift from driving to resource-efficient modes. Oregon has targets to reduce light-duty vehicle travel 20 percent by 2040. Minnesota has targets to reduce vehicle travel 14 percent by 2040 and 20 percent by 2050. Colorado and Ireland require major transportation projects to support emission reduction targets.

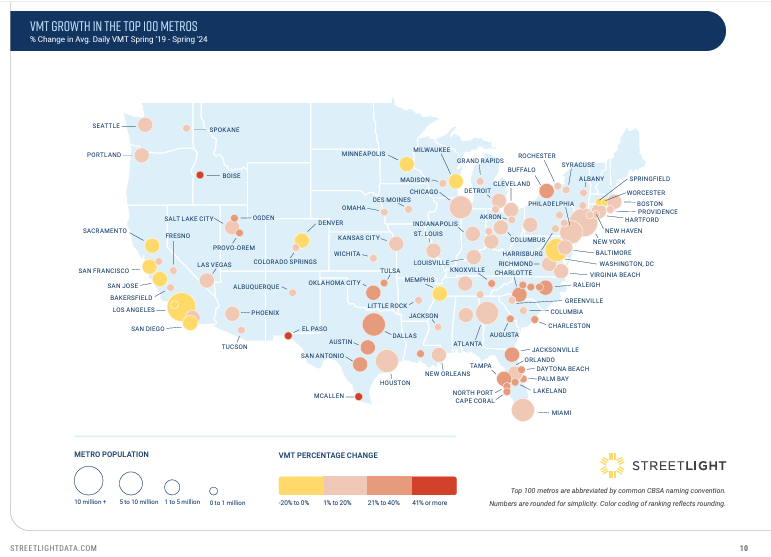

Recent data indicates that these jurisdictions are making progress toward those targets. Although vehicle travel grew in most U.S. metropolitan regions during the past five years, many California, Washington, and Colorado regions had reductions in per capita VMT. Los Angeles, Oxnard-Ventura, San Francisco, and San Jose experienced particularly large total vehicle travel declines, while Denver, Minneapolis, Portland, and Seattle had VMT growth below their population growth rates, as illustrated below.

2019 to 2024 VMT Growth Rates (Streetlight 2024)

These regions benefit from reduced consumer costs, traffic and parking congestion, road and parking infrastructure costs, crashes, and pollution emissions than would have occurred if VMT had grown at national levels.

Planners have a professional obligation to respond to future consumer demands and community needs. An important first step is to reform the way we predict future travel demands to avoid harmful self-fulfilling prophecies.

For more information see:

Caltrans (2020), Vehicle Miles Traveled-Focused Transportation Impact Study Guide, California Department of Transportation and the SB 743 Implementation Resources website.

CAPCOA (2021), Handbook for Analyzing Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions, California Air Pollution Control Association.

Kevin DeGood and Michela Zonta (2022), “Colorado’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions Rule for Surface Transportation Offers a Model for Other States and the Nation,” American Progress.

Eltis (2021), Planner’s Guide to Sustainable Urban Mobility Management (SUMP) and a Toolbox for Mobility Management,

F&P (2022), Providing VMT: Getting Beyond LOS, Fehr & Peers (www.fehrandpeers.com); at. Also see the SB743 Website (www.fehrandpeers.com/sb743) and the VMT+ Tool.

ITE (2023), Vehicle-Miles Traveled (VMT) as a Metric for Sustainability, Institute of Transportation Engineers.

Amy E. Lee and Susan Handy (2018), “Leaving Level-of-Service Behind: Implications of a Shift to VMT Impact Metrics,” Transportation Business and Management.

Todd Litman (2024), Are Vehicle Travel Reduction Targets Justified?, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Todd Litman and Meiyu Pan (2023), TDM Success Stories, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Todd Litman, Ousama Shebeeb and Ronald T. Milam (2024), “VMT as a Metric of Sustainability: Why and How to Implement Vehicle Travel Reduction Targets,” ITE Journal.

Carlton Reid (2022), “Major New Roads in England May Have Funding Pulled if They Increase Carbon Emissions or Don’t Boost Active Travel,” Forbes.

SUM4All (2019), Catalogue of Policy Measures Toward Sustainable Mobility, Sustainable Mobility for All.