World

The scientists making the ‘most sustainable protein’ out of thin air

By feeding a microbe with carbon dioxide, hydrogen and some minerals, and powering the process with electricity from renewable sources, the company has managed to create a protein-rich powder that can be used as a milk and egg substitute.

“We can source our main feedstock for the microbe from the air,” Solar Foods chief executive Pasi Vainikka says, as he gives a tour of the company’s facilities.

“We have started the production of the world’s most sustainable protein.”

Founded by Vainikka and Juha-Pekka Pitkanen in 2017, Solar Foods launched the “world’s first factory growing food out of thin air” in April.

“Much of the animal-like protein of today can actually be produced through cellular agriculture and we can let agricultural land re-wild and thereby build carbon stock,” Vainikka says, referring to the process whereby forests and soil absorb and store carbon.

Producing one kilogram of the new protein, dubbed “solein”, emits 130 times less greenhouse gases than the same amount of protein from beef production in the European Union, a 2021 scientific study claimed.

Vainikka navigates his way through the factory’s laboratory and into the control room, where a dozen people at computer screens monitor the production process.

“These are our future farmers,” he says.

Transforming food production and consumption is at the heart of combating the climate crisis and preventing biodiversity loss, according to Emilia Nordlund, head of industrial biotechnology and food research at Finland’s VTT Technical Research Centre.

Current projections show the consumption of meat is expected to increase in coming years.

“Industrial food production, especially livestock production, is one of the biggest causes of greenhouse gas emissions (and) the biggest cause of biodiversity loss, eutrophication and freshwater usage,” Nordlund says, eutrophication being the process by which water becomes nutrient-rich, leading to excessive growth of algae and other plants.

New food production technologies can help cut emissions and “decentralise and diversify food production”, she says.

“However, at the same time, we must improve the existing food production methods to make them more sustainable and resilient,” she adds.

Fermentation technology used to produce different nutrients, such as proteins, has been around for decades. But the field has expanded significantly in recent years with new technological solutions and research projects emerging worldwide.

Some of the most active start-up hubs focusing on cellular agriculture are in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands and Israel, Nordlund says.

“We are in a crucial phase as we will see which start-ups will survive,” she says, adding that stalling bureaucracy was slowing cellular agriculture’s take-off in the EU.

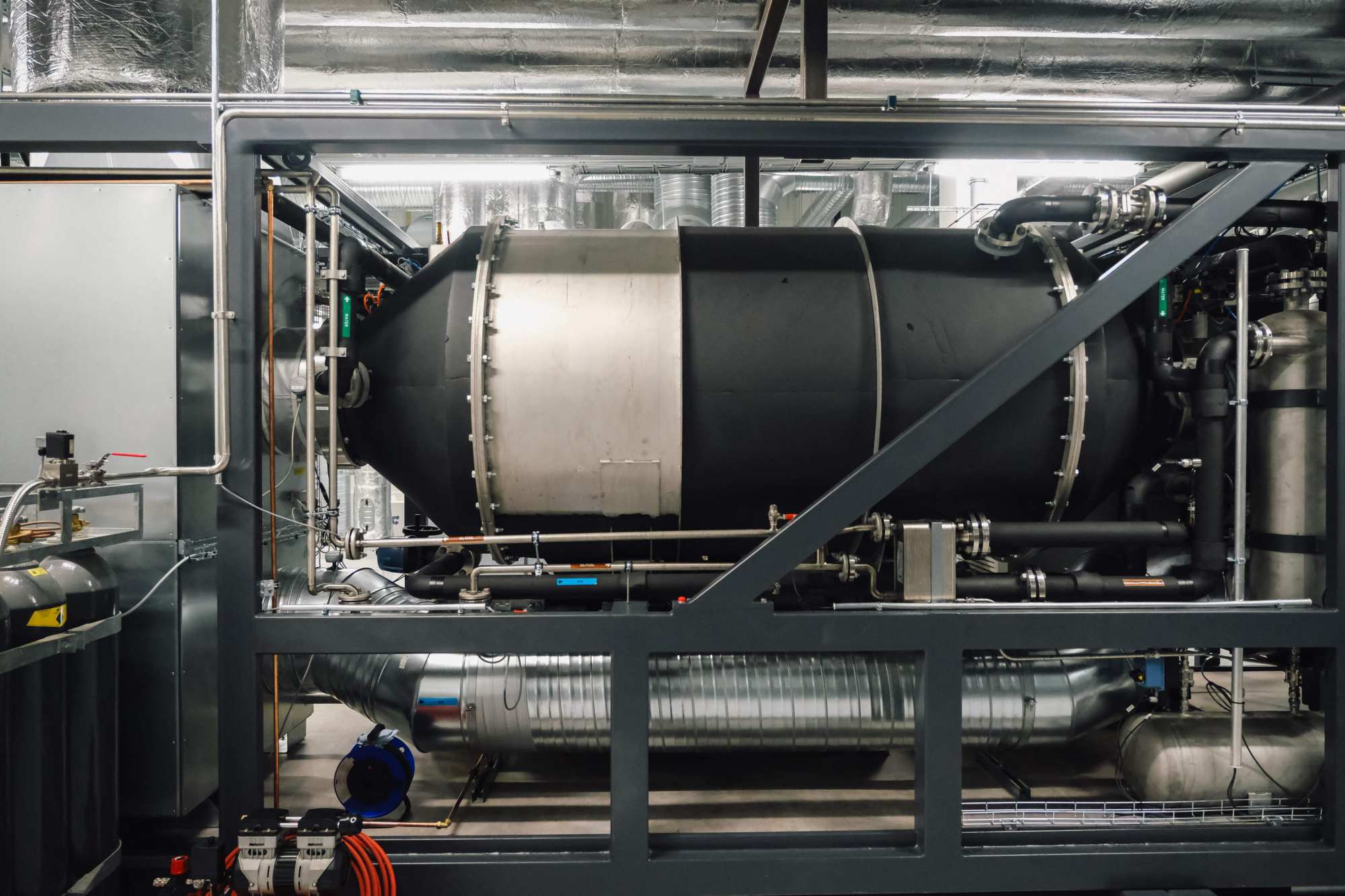

Dressed in protective gear to prevent bacterial contamination in the factory, Vainikka shows off a giant steel tank in a shiny production hall.

“This is a fermenter holding 20,000 litres [5,300 gallons],” he says, explaining that the microbe multiplies inside the tank as it gets fed the greenhouse gas.

Liquid containing the microbes is continuously extracted from the tank to be processed into the yellowish, protein-rich powder with a flavour described as “nutty” and “creamy”.

“The fermenter produces the same amount of protein per day as 300 milking cows or 50,000 laying hens,” Vainikka says.

That equals “five million meals’ worth of protein per year”.

For now, the main purpose of the small Finnish plant, which employs around 40 people, is to “prove that the technology scales”, so it can attract the necessary investments pending European regulatory approval.

While the protein has been cleared for sale in Singapore, where some restaurants have used it to make ice cream, it is still awaiting classification as a food product in the EU and the US.

To have any real impact, the aim is to “build an industrial plant 100 times the size of this one”, Vainikka says.