Next time you worry your collecting habit is getting a bit out of hand, you can try consoling yourself with the knowledge that the sun is a bit of a collector, too.

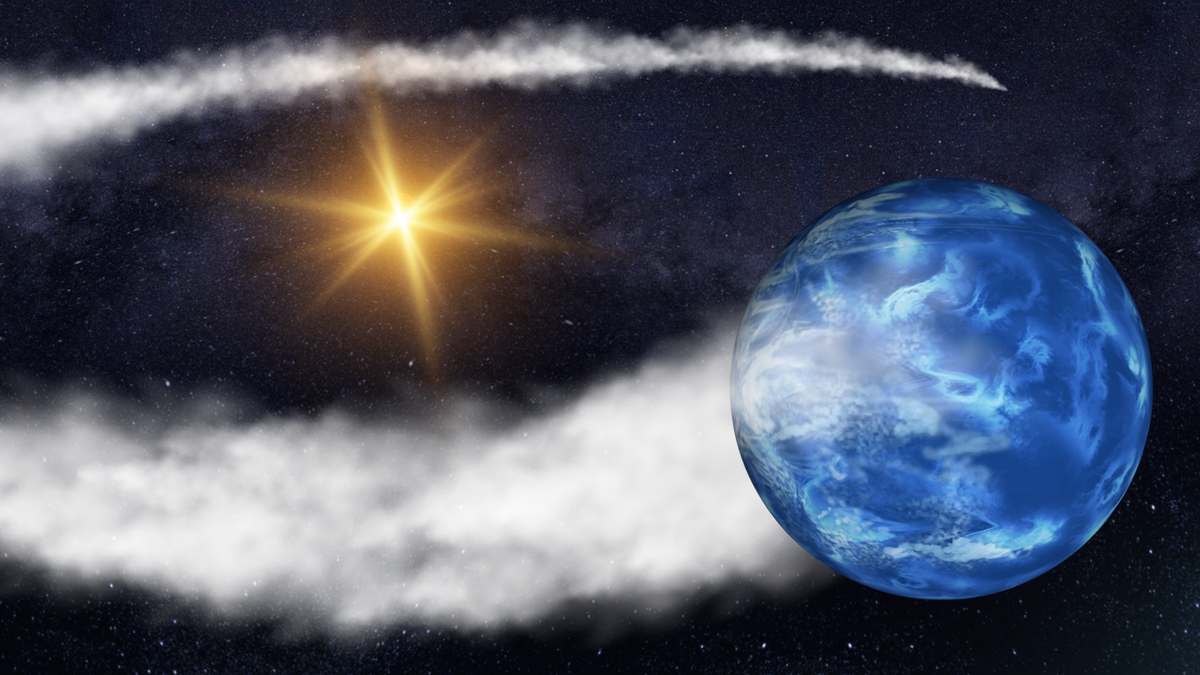

But, rather than hoarding comic books (guilty as charged), baseball cards, vintage trainers, or Pokémon cards, the sun snatches up passing rogue planets — and it isn’t picky. The sun is capable of grabbing small planets as well as Jupiter-size gas giants that get too close; our star then keeps them at the edge of the solar system.

As any collector will tell you, one of the key parts to any collecting hobby is trading — and the solar system does this, too.

It is capable of exchanging its prized rogue planets with those snatched up by its neighboring star system, Alpha Centauri. And new research suggests runaway worlds taken in by the solar system could orbit its outskirts for billions of years before moving closer to the sun and potentially cause chaos in the inner solar system.

Related: Rogue planets may originate from ‘twisted Tatooine’ double star systems

Scientists have suspected for some time that the solar system can grab objects that drift past, like comets and asteroids, collecting them beyond the Oort cloud, which is believed to be a spherical shell of trillions of icy bodies at the outer edges of the solar system.

The new research shows this “capture region” extends far beyond the Oort cloud, however, which is about two light-years from Earth (about 126,000 times the distance between Earth and the sun). The work also reveals that our planetary system is capable of drawing in bodies much bigger than comets or asteroids.

“We found that when objects are captured into our solar system, the distance to which they can be captured is far more than what was previously thought,” Edward A. Belbruno, research author and a Yeshiva University professor of mathematics told Space.com. “We found that objects that can be captured from about 3.81 light-years away, which is close to the next star system, the Alpha Centauri system.”

While our solar system wouldn’t be able to capture an object with a mass around that of the sun or greater, as this would affect the sun’s gravitational influence, it is capable of collecting rogue planets with masses reaching that of Jupiter, which is a thousand times less massive than the sun.

“It’s a very interesting result,” Belbruno continued.

Adopting a cosmic orphan

Rogue planets are worlds that have been ejected from their own planetary systems. This can happen when a passing star interferes with the gravitational stability of a planetary system or just through natural turmoil in a young stellar system.

The Milky Way is estimated to be populated with a huge number of free-floating rogue planets. Our galaxy may contain as many as a quadrillion (10 followed by 14 zeroes) rogue planets that have been ejected from their home systems to wander the Milky Way as cosmic orphans.

While much research focuses on how rogue planets can be ejected, fewer studies concentrate on the possibility that these celestial orphans can find new homes.

The duo of scientists behind this research, including ex-NASA expert James Green, discovered something surprising about this capture of passing rogue planets. There are actually two gravitationally stable points, or “Lagrange points,” at which ensnarement can occur, Green realized.

“You have two whole regions, little openings, where things can come into the solar system at those two Lagrange points,” Belbruno said. “One points toward Galactic Center; one points away from it.”

The mathematics professor, with a passion for celestial mechanics, explained that when rogue planets do enter the solar system at these openings, they will first start to move very slowly around our sun, holding a distance of about 3.81 light-years for around 100 million years. After this period, they will begin to spiral inward, a process that could take billions of years.

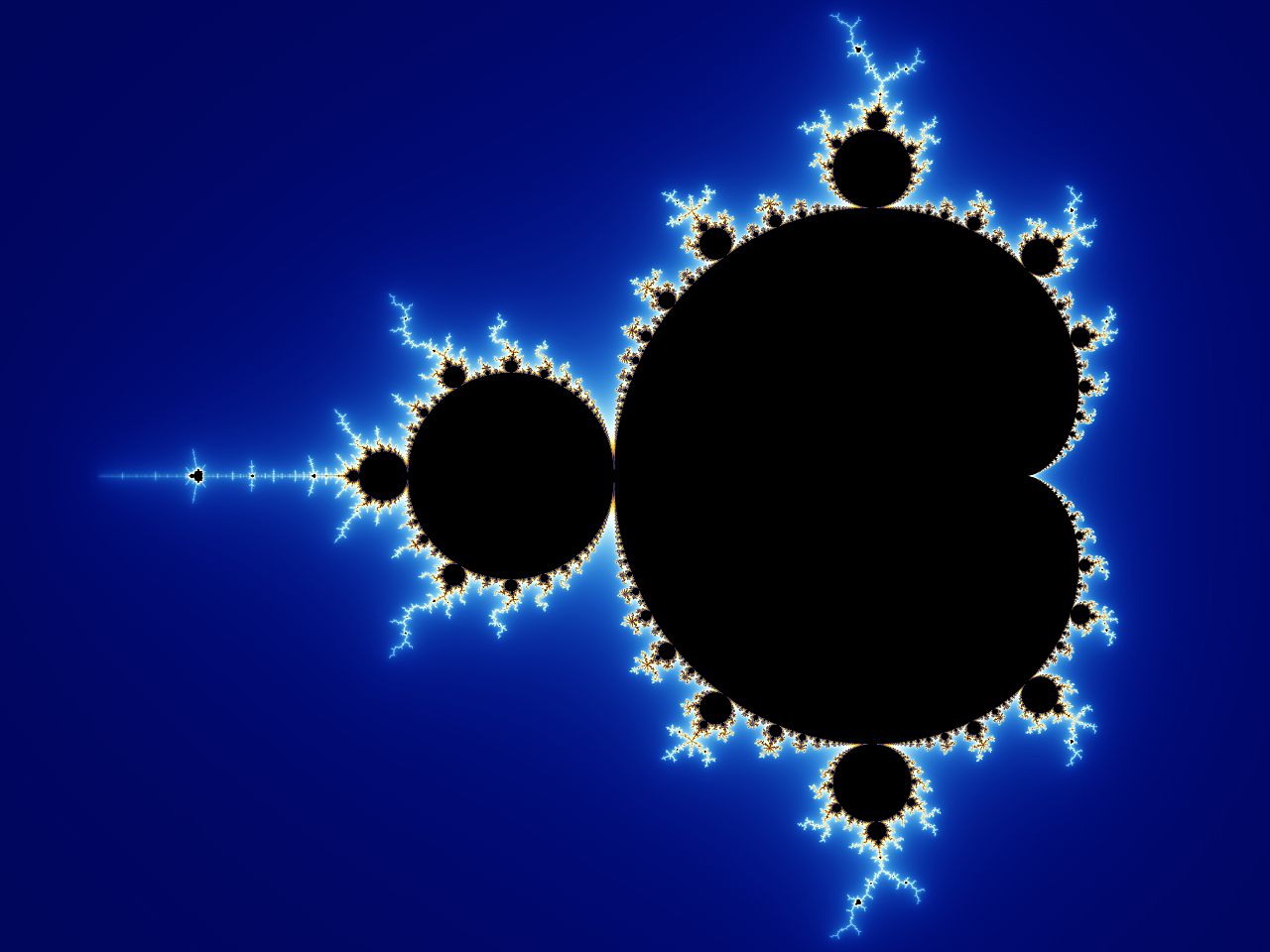

Belbruno explained that one interesting factor he and Green found regarding this migration is that the new addition to the solar system will orbit in a pattern called a “fractal curve.” This is a mathematical curve with a shape that repeats the same pattern of irregularity as it gets magnified. A famous example of this is the Mandelbrot set. “You get these really cool-looking curves, especially as the object gets closer and closer to its capture location,” Belbruno explained.

Gotta catch ’em all!

While the sun isn’t picky about the mass of planets it captures, it does have one criterion for its orphan planet collectibles.

Belbruno explained that for a rogue planet to be captured, it would need to travel at a relatively slow speed of a few hundred miles per hour. That is extremely fast by Earth standards, but it is a cosmic crawl considering that runaway planetary-mass objects have been detected moving at upwards of 1.2 million miles per hour (1.9 million kilometers per hour).

The slow velocities of these captured rogue planets means there could be a veritable reservoir of such objects orbiting the sun for billions of years (at distances up to 3.81 light-years).

As for what would happen if a captured rogue planet worked its way into the solar system? Well, Belbruno said this effect would depend on the size and mass of that planet.

“Let’s suppose that world was the size of Jupiter and came drifting into the solar system,” he said. “A Jupiter-size object coming into our solar system would cause orbits to shift dramatically in some sense. It would cause immediate effects on the dynamics of the Earth’s motion around the sun, and that would definitely affect life on this planet.

“It is not inconceivable that this could have some planets of the solar system go rogue themselves.”

Of course, the rogue planet may never make it to the inner solar system. As mentioned above, orbiting the sun at a distance of 3.81 light-years would bring a captured rogue planet awfully close to Alpha Centauri, which can catch its own rogues and hold them at a distance.

That means the two star systems could exchange their captured rogues, like kids trading baseball cards.

“Our solar system’s gravity goes out close to that of Alpha Centauri, so this would mean that Alpha Centauri’s capture zone goes very close to that of our own sun’s,” Belbruno said. “The two systems are completely overlapped in terms of gravitational effect, and this means that objects going back and forth would be very, very natural.”

The scientists’ work is currently based on mathematical modeling, with Belbruno pointing out that, because rogue planets emit little light, spotting one out past the Oort cloud would be extremely difficult.

One helpful factor in the search is the fact that Belbruno and Green pinpointed the two capture locations, with these Lagrange points a natural place to start hunting for adopted orphan planets. Such a search may be currently beyond the ability of telescope technology, though the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) could conceivably spot thermal emissions of such a world in infrared light.

“Many objects could be out there in holding patterns, sort of spiraling around the sun,” Belbruno concluded. “If they come in, they can’t get out — even if they entered the solar system 4 billion years ago. It’s definitely possible there are captured rogue planets already out there.

“We just don’t know.”

A preprint of the study can be viewed on the paper repository arXiv.