Travel

This Is What Space Travel Does to your Body » Explorersweb

With one astronaut hospitalized after a delayed return and another’s weight loss the subject of tabloid speculation, it’s been a busy month for NASA public relations. In June, a series of issues with Boeing’s Starliner rocket stranded two astronauts on the International Space Station until February of 2025 at the earliest. Likewise, a four-person crew intended to return to Earth in August only made it back in late October.

Upon returning, one of the four was hospitalized overnight. Many articles over the last few weeks have suggested that NASA is hiding debilitating health issues in its astronauts. Medical privacy protocols keep their health secret, fueling these rumors.

Which of the four returned astronauts was hospitalized? What for? And has Suni Williams, one of the two astronauts stuck on the ISS until February, lost a concerning amount of weight?

Although neither Williams nor the hospitalized astronaut has caught a mysterious alien disease, there’s a dash of reality in every conspiracy. Being in space changes your body — often drastically. So let’s take a look at the very real medical effects of life in the void.

Welcome to zero gravity

Humans evolved in a ridiculously specific niche. We need temperatures between about -30 to +50 °C, oxygen levels between 15% and 20%, and protection from all radiation more energetic than the near-UV. In the grand scheme of the universe, we’re spoiled rotten.

And for as long as humans have been humans, we’ve been putting ourselves in environments we didn’t evolve to survive. Space wastes no time in letting us know we don’t belong. As soon as astronauts leave Earth, they lose the gravitational tug on their inner ear that tells their brain how to balance.

The effect is like motion sickness, when the body starts moving in ways the mind doesn’t anticipate. That’s why carsickness tends to be worse in the back seat, where the headrest in front appears stationary. The contrast is even more drastic on the ISS. The eyes tell the brain it’s standing still, while the inner ear insists it’s in free fall.

“Space sickness” isn’t a new problem. In fact, Gherman Titov, the second man ever in space, threw up inside his shuttle.

A Moldovan stamp featuring cosmonaut Gherman Titov, the second man in space and the first to throw up from space sickness. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Puffy faces and lazy hearts

Right as a new astronaut adjusts to the sensation of falling, the face begins to swell. Human circulatory systems are designed to constantly fight gravity. On the surface of the Earth, the heart fights hard just to keep blood flowing, and even then, blood naturally congregates in the lower extremities.

When gravity vanishes, blood distributes evenly throughout the body. The face swells. Unlike space sickness, which tends to abate after a few days, astronauts’ faces stay swollen throughout the mission.

But there are deeper effects than just cosmetic. The heart deteriorates rapidly in zero gravity. All of a sudden, the force it spends its existence opposing disappears. It gets lazy. In space, the blood practically pumps itself.

Heartbeats become irregular. When the heart does beat, it contracts with less strength. And at the cellular level, mitochondria swell and break up while proteins fragment. Genes related to heart disease start to activate.

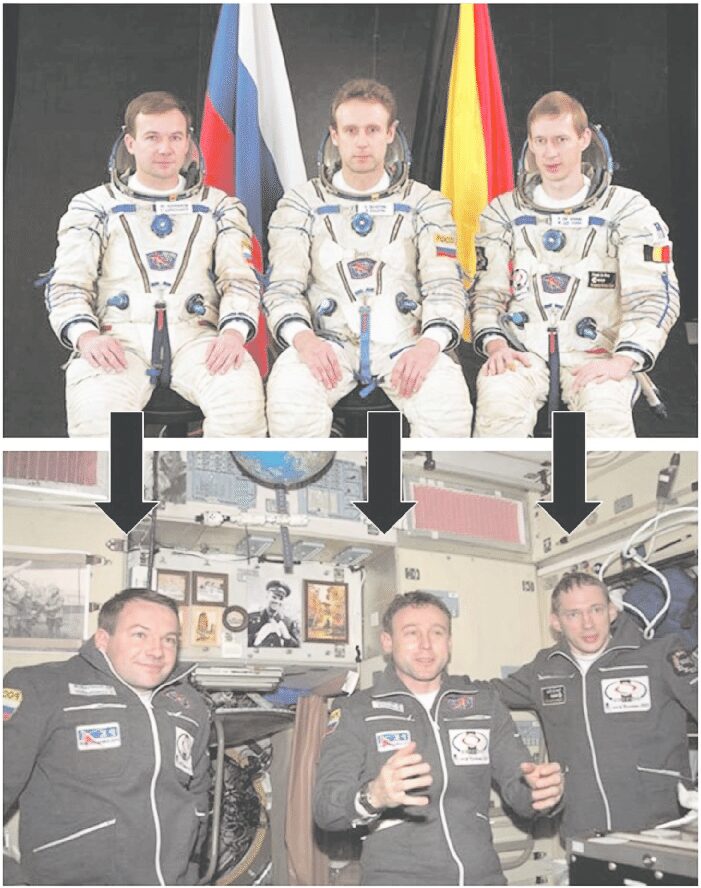

Upper photo: the crew of the 2002 Odissea Mission on the ground. Lower: the crew in space. Photo: ESA

Chicken legs

Down at the other end of the body, the legs are in limbo. Less oxygenated as blood strays up to the face, they are also freed from having to support the body. That’s why astronauts work out for two hours a day, trying to keep the legs and lower back active enough to prevent injury upon returning to Earth.

Even with the exercise, astronauts face nearly a three times higher chance of a herniated disk after their stay in space. That’s when the cartilage inside the spinal column squeezes out between vertebrae, often pinching nerves.

Astronaut Luca Parmitano exercises on a treadmill in zero gravity. Photo: NASA

Cosmic radiation spells cellular trouble

The atmosphere on Earth does more than set the climate and provide breathable air. It also shields us from the majority of high-energy radiation that can ionize our cells, leaving us vulnerable to genetic glitches like cancer.

In space, there’s no such protection. Even in the thin upper layers of the atmosphere, airplane flight crews suffer 24% higher rates of cancer than the general public. Although scientists haven’t quite whittled down all the possible factors that could contribute to this, the dominant theory is cosmic radiation. (Frequent flyers, fear not — you have to fly daily for this statistic to apply.)

If tracing the effects of energetic photons on flight crews is hard, it’s even harder on astronauts, a population numbering not even 700. That’s nowhere near enough for a statistically sound health study. But some odd patterns are starting to emerge at the genetic level.

Researchers found that even after a nine-minute stay in space, the DNA called telomeres, which protect the ends of chromosomes, had stretched on all members of the SpaceX civilian mission Inspiration4. Likewise, a study comparing astronaut Scott Kelly to his identical twin and fellow astronaut Mark Kelly (now a senator of Arizona) found his telomeres stretched in space and snapped back to normal on the ground, slightly shorter. Since telomeres generally shorten with age, it’s not clear what effect this stretching and reversal has on long-term health.

What’s driving this strange chromosome behavior? It could be microgravity, but the authors of the study on the Kelly twins suspect that radiation damage is at play.

Astronaut Scott Kelly, left, recently revisited space as part of a genetic study. Right, his identical twin, retired astronaut Mark Kelly, who participated as the control subject while serving as a senator for the state of Arizona. Photo: NASA/Alamy

We don’t know what we don’t know

As of right now, limited datasets and confounding factors paint a muddy picture of the long-term impacts of space travel. Even when space agencies gather information for the protection of astronauts, they often have to keep it secret to comply with medical privacy laws. The study of the Kelly twins, for instance, may never have its full results released while the subjects are alive.

The first photo that comes up for the search ‘Suni Williams,’ taken of the astronaut in 2004. Photo: NASA

Medical privacy

As for Suni Williams and the mysteriously hospitalized astronaut, NASA is clear on the matter. The secrecy is due to medical privacy, and everyone is fine. The four crew members who returned in October are fine, Suni Williams is fine, and everyone else on the ISS is fine.

Given that the hospitalized astronaut was discharged after only one night, there’s no reason to suspect deception beyond the requirements of medical practice. One of the returned astronauts, Michael Barratt, promised the public will know what happened one day.

“In the fullness of time, we will allow this to come out and document it,” he told The New York Times. “For now, medical privacy is very important to us.”

The internet obsesses over an astronaut’s weight

Meanwhile, Suni Williams has spent the last few days reassuring people that she’s healthy. After NASA released a series of photos including her, online commenters and tabloids fixated on her looks. Multiple pieces quoted unverified sources, purporting to be from within NASA, who claimed she had lost a concerning amount of weight.

The woman herself, however, states that her weight is the same, although her body has changed in outer space. Her workout regime on the ISS, she says, has made her butt bigger.

Suni Williams is 59 years old — 17 years older than the average for female astronauts. Between societal prejudices against older women, odd angles in photographs (see the pizza-making photo below, where the camera distorts the proportions of both people in frame), the propensity of the press to obsess over women’s bodies, and the simple fact that peoples’ appearances often change considerably since Wikipedia photos taken 20 years before, there are a lot of mundane reasons why the buzz around Williams is based in nothing.

A photo of Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore prompted rumors about Williams’ health. Photo: NASA

It’s easy to imagine the sort of things that might have sent an astronaut to the hospital after landing. Tachycardia or severe dizziness could both ensue from a weakened heart. Legs could tremble after so many months in space. Or perhaps nausea sets in as the world doesn’t move like the mind expects it to. For the first time in a long while, the inexorable force of gravity drags the inner ear back down to Earth.