World

This Is What the World’s First All-EV Car Market Looks Like

To keep pace with the changing market, Norwegian fuel station operators like Circle K are investing in chargers even in non-urban sites like in Minnesund. Photographer: Naina Helén Jåma/Bloomberg

Norway is on the cusp of completing a transition away from combustion cars thanks to targeted incentives that made electrics an easy choice.

In Norway, Toyota Motor Corp. is going from one electric-powered model to five to better compete with Tesla Inc., fuel stations are ripping out pumps to make space for chargers, and even nursing homes in the rural interior have switched to battery-powered cars despite months of arctic cold.

All are signs of the dramatic shift that has put the Nordic country on the cusp of becoming the first market in the world to all but eliminate sales of new combustion-powered cars.

“It’s cold here, there are mountains, long distances to drive,” Yngve Slyngstad, the former head of Norway’s $1.8 trillion sovereign wealth fund, said on the way to his electric car in downtown Oslo. “There are so many reasons EVs shouldn’t have been a success here, and yet we’ve done it.”

It’s a transition that happened with remarkable speed. While there have long been incentives to encourage EV purchases — mainly to promote short-lived domestic upstarts — adoption only started to accelerate in recent years, as a greater variety of cars became available. Once an inflection point was reached, the ramp-up was rapid.

Despite winding back some tax benefits, EVs accounted for 94% of new car sales in October — almost double the rate in China — putting the country within reach of a goal to stop adding combustion engines next year.

Norway’s progress is bucking trends elsewhere. In Europe, sales have declined this year, while in the US, the re-election of Donald Trump represents a risk to the country’s halting progress toward zero-emission vehicles.

Norway had advantages that helped propel the transition — not the least being its oil and gas wealth — as well as successive governments that were aligned on the need to reduce transport emissions. But its cold climate and low population density were hurdles. It’s also a mature market, which meant changing ingrained habits and making it an important test case for other developed countries.

“This market is not a big market in terms of the volume, but in terms of the lessons that are then applied for the future, it’s huge,” said Piotr Pawlak, president at Toyota Norway.

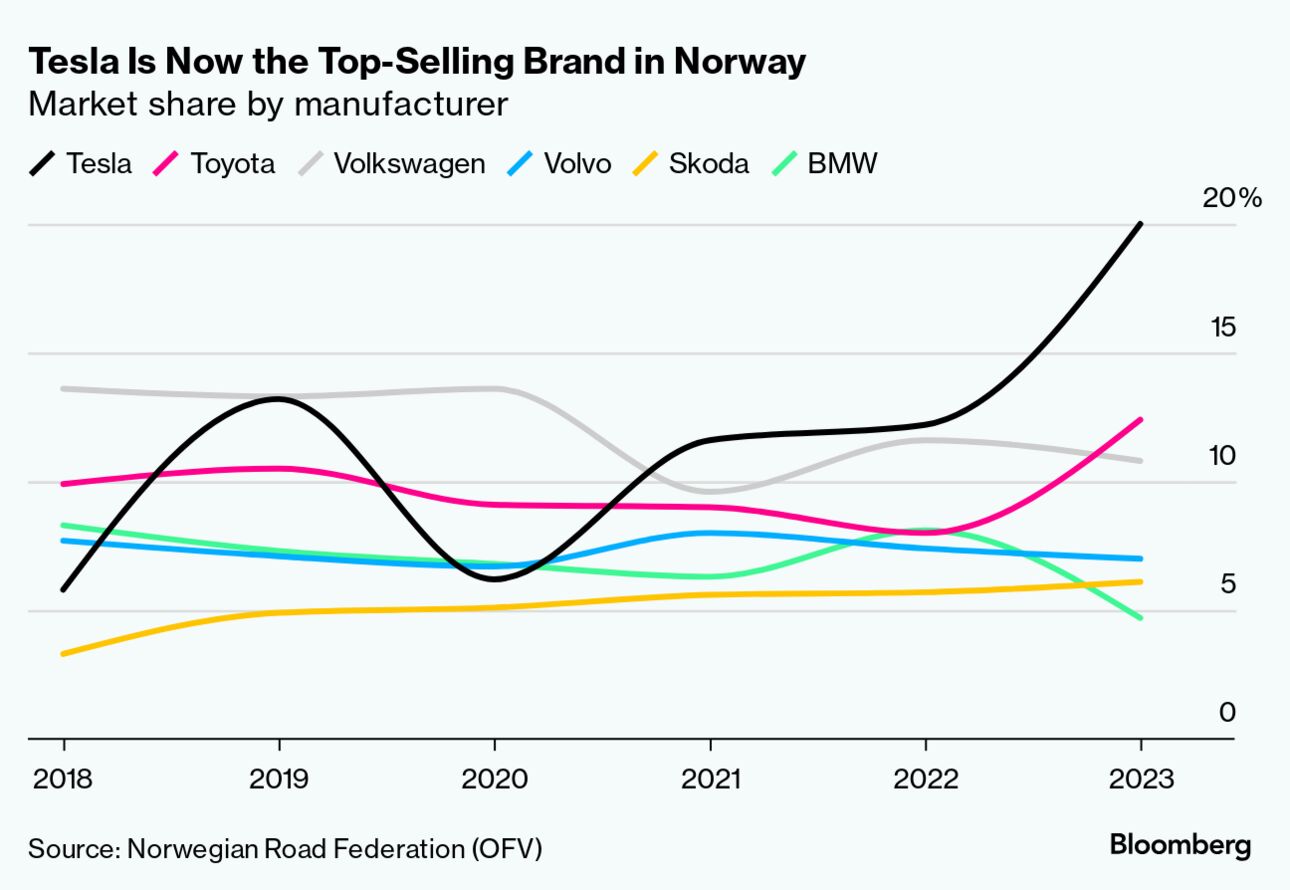

Tesla Is Now the Top-Selling Brand in Norway

Market share by manufacturer

Source: Norwegian Road Federation (OFV)

The gradual end of the combustion-engine era has caused large and small changes. In the auto industry, Tesla has replaced Toyota and VW as the nation’s most popular brand, and Chinese manufacturers like Nio Inc. and BYD Co. are expanding. There are now more than 160 electric models available, compared with less than 10 a decade ago.

Fueling stations have had to rethink their business model. Repair shops have had to invest in high-voltage facilities, but are also under pressure to service more cars because it takes less time to fix an EV.

At automotive chain Moller group, open battery packs require the expertise of a high-voltage technician. Photographer: Naina Helén Jåma/Bloomberg

There are also issues that have yet to be sorted out like what happens to batteries after an electric car gets scrapped. And despite Norway’s success, combustion cars still account for about three out of four cars on the road. As for commercial vehicles, the transition has only just started.

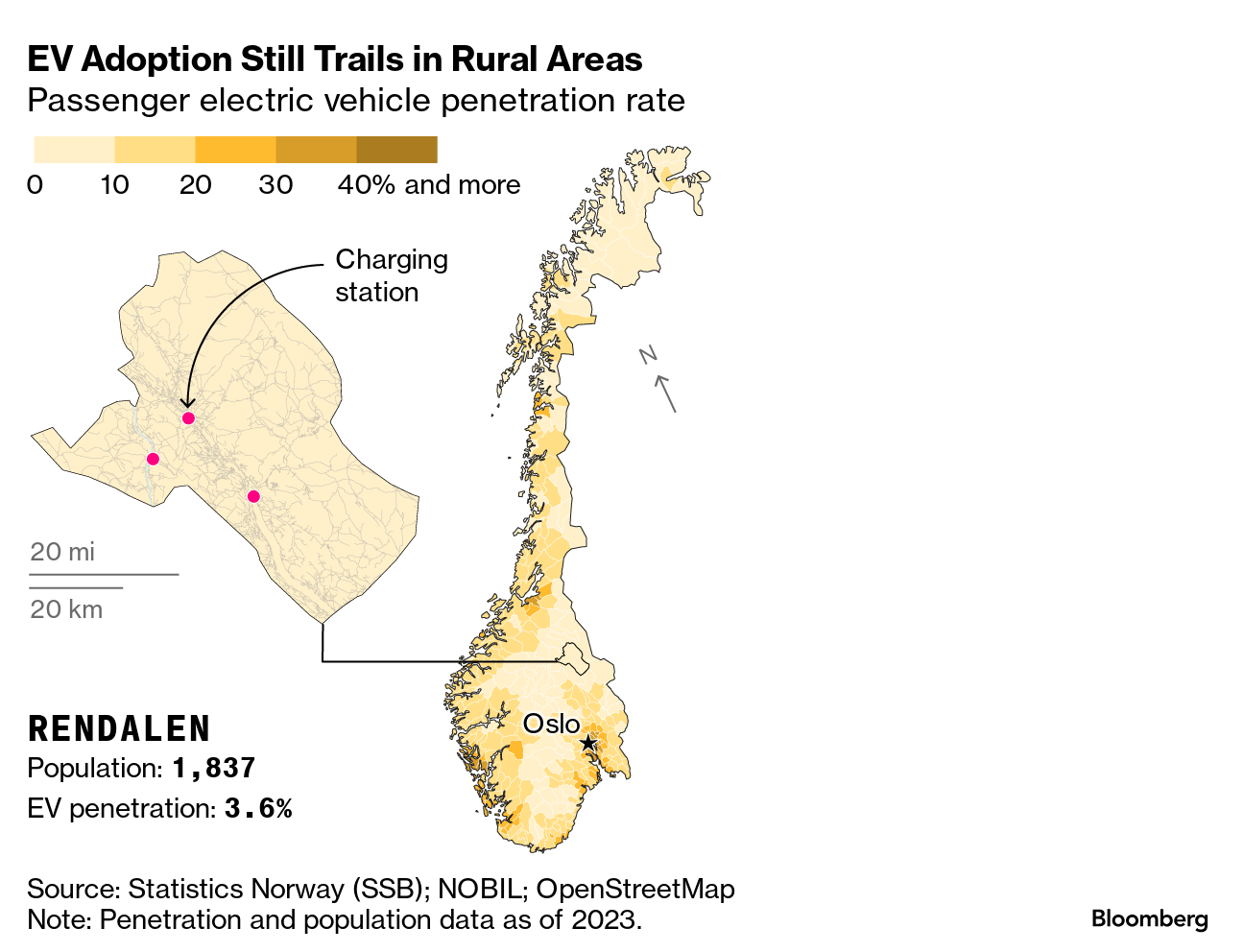

To explore what the shift means, Bloomberg went from remote Rendalen, where EV penetration is one of the lowest in the country, to Oslo, where combustion-powered cars are getting crowded out.

In the sparse interior of Norway, roads weave through mountains and dense evergreen forests and towns are few and far between.

In the valley of Rendalen, there’s a museum dedicated to the region’s rugged history, which is open only from July through early September when there’s less risk of visitors getting stranded in snow and ice. And yet even here, the future of the auto industry has arrived, with two bright green chargers in the parking lot.

EV Adoption Still Trails in Rural Areas

Passenger electric vehicle penetration rate

Note: Penetration and population data as of 2023. Source: Statistics Norway (SSB); NOBIL; OpenStreetMap

The municipality also bought seven electric compact SUVs from Toyota, mainly for medical staff from the local nursing facility to use for home visits. They arrived last summer and performed well through the first winter, according to Tore Hornseth, Rendalen’s business manager.

“There was probably more skepticism than what was needed,” Hornseth said. “It’s always a bit like that.”

But doubts are still evident at May & Fred’s Fish and Leisure in the nearby village of Akrestrommen. Sondre Bjornstad Noren, a wildlife-management student who works part-time at the store, said he uses his old VW wagon rather than his father’s EV when they go fishing, because it can handle rough roads and is more practical.

Local concerns include distances between chargers and risks associated with a dead battery, according to land-use consultant Frank Engene, who regularly uses his diesel-powered Kia to get out into the woods with his Norwegian elkhound Tyril.

“My car is working well so I don’t feel the need to change it,” he said.

Sondre Bjornstad Noren opts for his combustion-powered VW wagon when heading into the backwoods on fishing trips. Photographer: Naina Helén Jåma/Bloomberg

That sentiment is reflected across the country. Cars in Norway have been gradually getting older as people hold on to conventional models, even if they’re not buying new ones. The average age of a gasoline-powered car has risen to 19 years from 16 in 2020. It’s a similar story for diesels, according to OFV, the national road federation.

Sales of second-hand conventional models have decreased this year, signaling that people are keeping them. Even so, the numbers are declining, with 1 million fewer gasoline cars on the road in Norway compared with 20 years ago. And they’re being used much less, covering a quarter of the miles and consuming 70% less fuel.

Diesel demand has been slower to fall, primarily because buses and trucks still rely on the fuel. The adoption rate of 29% in the commercial-vehicle segment is less than a third of that in personal cars because incentives aren’t as generous and fewer models are available.

While EVs still have issues to overcome, one of the key aspects of Norway’s successful transition is that it’s not forced.

“This is mostly about economics,” said Colin McKerracher, the Oslo-based head of transport analysis at BloombergNEF. “Behavioral barriers to adoption are much less of an issue than originally thought. When the economics are good, people buy EVs in large numbers.”

Road Map

The Nordic country’s push into EVs started in the early 1990s to support the home-grown Think City and Buddy. The electric models were boxy, had terrible range and were only for die-hards, according to Christina Bu, head of Norway’s electric car association.

While the startups ultimately failed, the policies remained in place and over the years other incentives were added: value-added tax was scrapped, the cars were given access to bus lanes, parking was cheaper and in many cases free, and drivers weren’t charged for using ferries or toll roads.

The overall package made the decision for EVs an obvious choice for a growing number of Norwegians. The government’s target for 100% EV sales, which was set in 2017 by a center-right government, was also never hard and fast. Gasoline and diesel vehicles can still be sold in 2025 and beyond — in contrast to the European Union’s plan to ban them by 2035.

Norwegian households initially tended to hold onto fossil fuel cars after buying a battery-powered model, but now almost two-thirds that own an EV don’t have a combustion engine back-up, according to the country’s electric car association.

The shift was accelerated as Norway’s new center-left government in 2021 imposed higher registration fees on combustion-powered vehicles. That added a stick to the carrots offered to adopt EVs once infrastructure was sufficient.

Christina Bu, general secretary of Norway’s EV association, has seen battery car sales go from about 3% to almost 100% during her tenure. Photographer: Naina Helén Jåma/Bloomberg

“It’s important to have the consumer’s voice at the table. In many other countries you don’t really have that,” said Bu. “There’s nothing in Norwegians’ mindset that has helped make this happen.”

But money has. The country, which isn’t part of the EU, has foregone billions in tax revenue, which in Norway’s case can be offset with fossil fuel income.

Waypoint

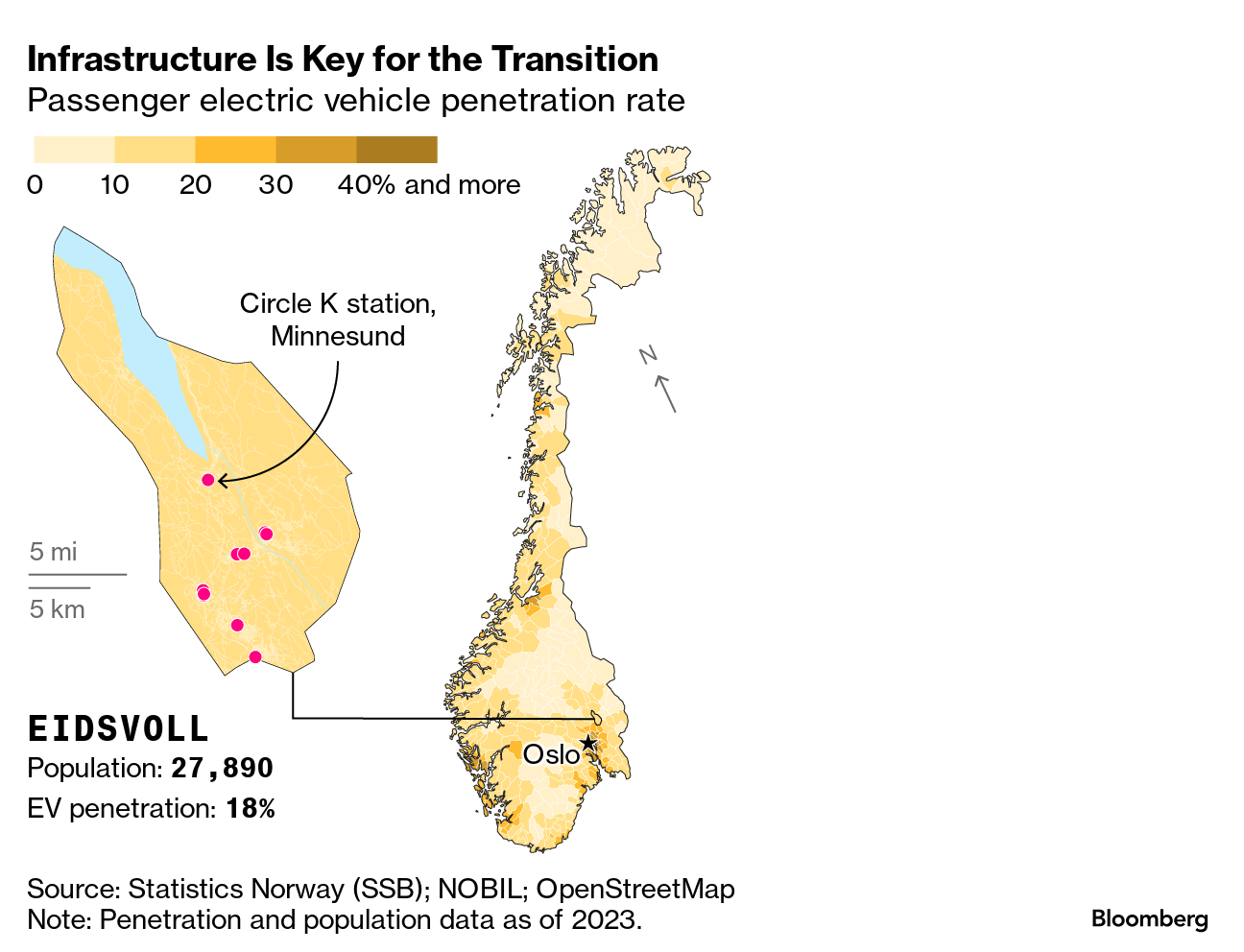

At the southern end of Lake Mjosa, a village with less than 500 residents is an unlikely place for a milestone in Norway’s EV transition. But Minnesund lies on a highway about midway between Oslo and the ski region around Lillehammer, and it’s here where Circle K installed its second-ever fast charger in the country in 2012.

Infrastructure Is Key for the Transition

Passenger electric vehicle penetration rate

Note: Penetration and population data as of 2023. Source: Statistics Norway (SSB); NOBIL; OpenStreetMap

“There were people wondering why on earth we had set up a charger here,” said Anders Kleve Svela, Circle K’s senior e-mobility manager, pointing to the spot on the far side of the parking lot. He recalled making a winter road trip at the time from Oslo in a Nissan Leaf to prove it was possible to cover the 70 kilometers (44 miles) without running out of power. “We just made it,” he said.

Costing about $140,000 per fast charger, Circle K’s expansion marks a significant investment, but the convenience-store chain has gone so far as to rip out fuel pumps in at least ten locations to add to its network of 1,020 chargers. Overall, Norway has 29,473 public EV chargers, according to BNEF. Its density of fast chargers is about one per 100 cars, compared with about 175 cars in the UK.

Since topping up a battery can take over a half hour, there’s greater sales potential per visit, but tapping that means upgrading amenities. Circle K spruced up seating areas, added plugs for laptops and phones and installed free wifi. Food selection has been broadened beyond grab-and-go items to include freshly made sandwiches and Norwegian staples like waffles and cardamom buns.

Tesla chargers at a hub in Nebbenes near Minnesund are tucked between a Shell gas station and outlets from a privately owned charging rival. Photographer: Naina Helén Jåma/Bloomberg

Circle K has upgraded the interiors of their stations and sees Norway as a “laboratory” to better understand the needs of EV drivers, said the company’s Global Head of E-mobility Haakon Stiksrud. Photographer: Naina Helén Jåma/Bloomberg

The municipality of Eidsvoll, where Minnesund is located, is roughly in the middle in terms of adoption. Expanding infrastructure is evident, but so are nagging obstacles. For instance, Circle K wanted to install truck charging at its site there, but couldn’t secure enough power.

Because of Norway’s pioneering role, drivers have had to struggle with teething issues, like standing knee deep in snow and trying to download a payment app. That should be resolved as of next year after the government required charging providers to accept credit cards.

The transition has also led to a shift in behavior like planning ahead on trips and bringing along work or entertainment to pass the time while charging or waiting to charge at busy times.

“I don’t think Norwegians have any more desire than Americans to stand in lines, but we’ve been forced to do it,” said Oyvind Solberg Thorsen, director of Norway’s road federation. “There is acceptance that that’s how it is.”

More battery models on the road mean more coming through workshops. While tires and brakes still need replacing, there are fewer oil changes and repairs are often faster or simply require a software update.

For automotive chains like Moller Group, the transition means new equipment such as protective clothing and lifting tables that can bear the weight of a vehicle with a 700-kilogram (1,500-pound) power pack.

Removing battery modules takes place in a separate workshop by technicians with the highest level of training. Almost all fixes can be made on site, unlike in the past when it wasn’t unusual to fly in specialists, according to Marius Hjorth-Martinsen, who oversees the 50 mechanics working at Moller’s Hvam workshop on the outskirts of Oslo.

“As these cars begin to get older, cells and complete batteries and electric motors have to be replaced,” he said. “It shows that we have to work on those cars as well.”

While technical glitches are more common than drained batteries – less than 3% of calls made to roadside assistance company Viking – not all issues have been resolved.

At the northern end of Lake Mjosa, Gronvolds Bil-Demontering has almost 700 wrecked cars in its lot and over a third are EVs. Many have battery packs that are still usable for energy storage, but only about half of the 282 in the salvage company’s warehouse will get resold, according to Chief Operating Officer Karl Morten Dalen.

“Customers should contribute to the costs of the recycling upfront,” he said. “Driving an electric car is only part of the environmental equation.”

Arrival

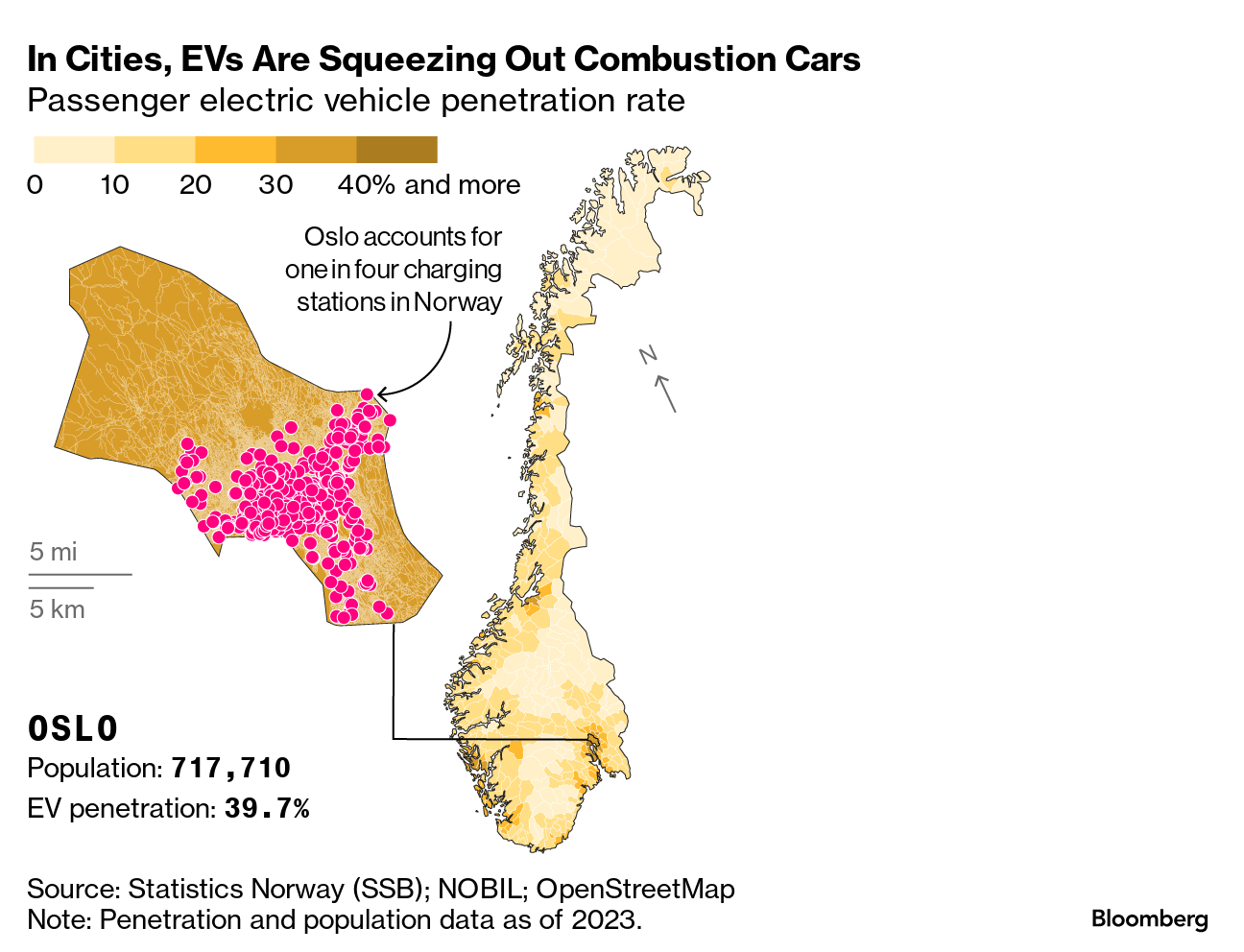

In downtown Oslo, the dominance of electric cars is hard to miss. Chinese brands Voyah, BYD, Hongqi and Xpeng jostle for prime real estate. At Nio’s showroom across from the Norwegian parliament, customers can sit fireside while sipping cappuccino with pictures printed on the foam.

In Cities, EVs Are Squeezing Out Combustion Cars

Passenger electric vehicle penetration rate

Note: Penetration and population data as of 2023. Source: Statistics Norway (SSB); NOBIL; OpenStreetMap

Nio’s country manager An Ho scouted locations for what would be the carmaker’s first European showroom little more than three years ago. At that time, there were still only a handful of Chinese brands in Norway, but now choices have ballooned.

“If you go to McDonald’s, you always find Burger King next to it,” Ho said. “Here in Oslo, it’s easier to walk around and compare because it’s close by. I think that’s a good thing.”

Legacy carmakers have jumped on the trend as well. Hyundai Motor Co. stopped selling fossil fuel models in Norway last year. The same is true for Stellantis NV’s brands including Peugeot, Opel and Fiat. Volkswagen’s Audi sells RS performance cars for enthusiasts, but otherwise is almost exclusively electric. Toyota will continue to sell hybrids, as it ramps up its EV offerings.

Norway’s biggest independent car retailers are also on board. Moller stopped selling conventional VWs in January. Bertel O. Steen is more pragmatic, but there’s little doubt that battery-powered cars are here to stay.

“Before you had to defend your choice if you wanted to buy an EV,” said Simen Heggestad Nilsen, general manager for Bertel O. Steen’s dealership in the Oslo suburb Lorenskog. “Now it’s the opposite.”

Oslo grid operator Elvia has to reinforce and expand electricity networks to accommodate demand, often with separate stations and transformers to serve isolated areas. But the overall strain is manageable as cars and buses often charge at non-peak times, according to spokesman Morten Schau.

With EVs accounting for 40% of the city’s car fleet, Oslo’s air quality has led to lower concentrations of smog-inducing nitrogen oxides. But the city is still struggling with particulate matter, mainly from road and tire wear. Battery models haven’t made the problem substantially worse, but haven’t made it much better either, said Tobias Wolf, the city’s chief engineer of air quality.

Electrifying road transport is “not a perfect solution,” he said from his office overlooking a boxy white testing station. “Air quality is complicated.”

On balance, Norway is proud of being the first country in the world to complete the switch away from combustion-powered cars, but there’s still room for nostalgia and the occasional joyride, which has helped ease the transition and kept resistance in check.

Frode Myhr, an art installer for Norway’s National Museum and a vintage-car enthusiast, mainly cycles around for transport, but still enjoys taking out his Ferrari. The reactions are mixed.

“Some are thrilled by the sound it makes, by seeing it. Others think I am wrecking the environment or hate the noise,” he said. “The other day, someone egged my car. I felt badly about that.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25813919/DSC00470.JPG)