World

To Save the World, My Mother Abandoned Me

When I was in grade school, my prized possession was a button. It went on my quilted coat in the winter, and my jean jacket in the spring, and when it got too hot, I’d reluctantly pin it to my book bag. This was the ’80s, and buttons featuring Smurfette or Jem were sartorial staples. Still, my button stood out. Vote Socialist Workers it said, and below that: GonzÁlez for Vice-President. It had a photograph of a woman’s face in profile: black hair, big glasses, ribbed turtleneck, determined look. My mother.

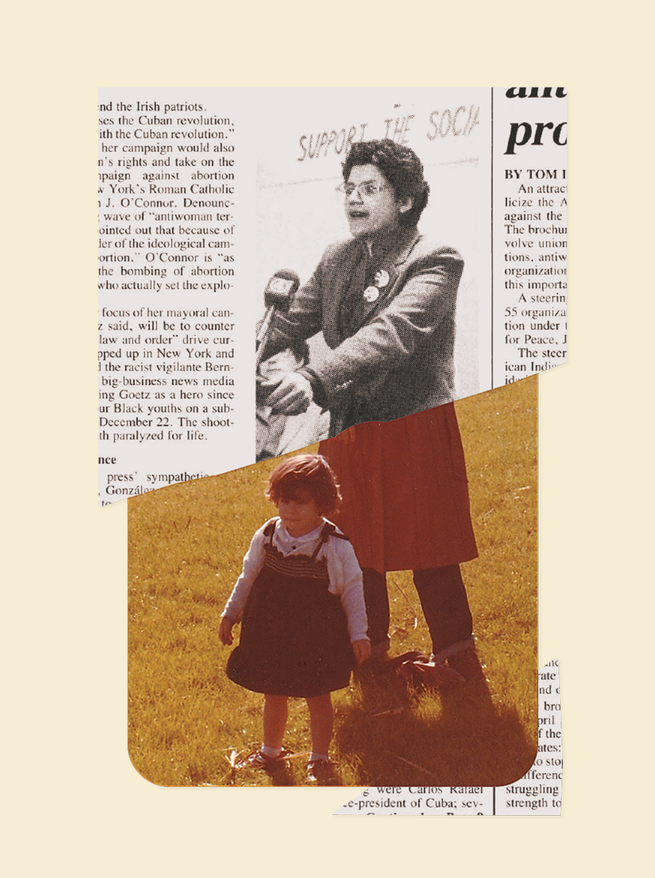

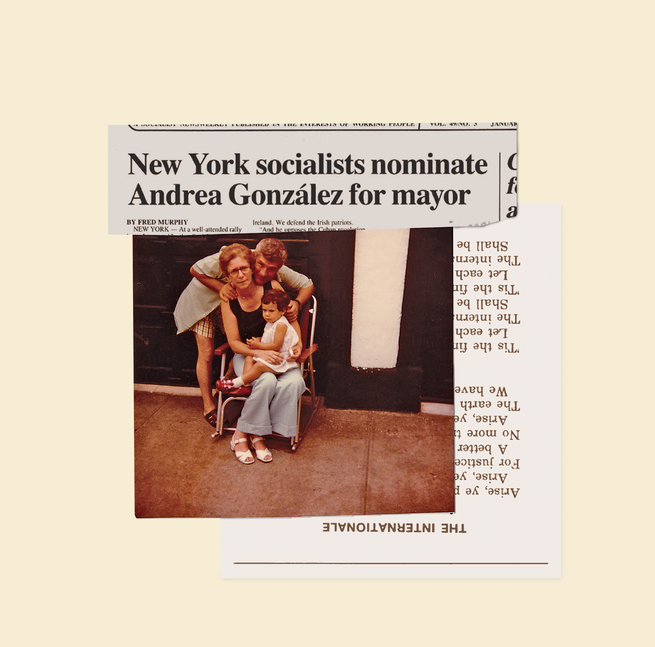

The button was a souvenir from her 1984 campaign for vice president of the United States—my mother, Andrea González, was the first Puerto Rican woman to run for national office. The day it came in the mail, I was 7 years old and hadn’t lived with her for nearly four years. Her running mate was a former Black Panther named Mel Mason. Obviously, they lost. But that didn’t make me less devoted to the thing. If asked—and I always hoped people would ask—I could rattle off the talking points of their platform.

Lots of kids don’t have mothers. The teachers at my Brooklyn public schools made sure we motherless children knew that we weren’t alone, that there were others whose permission slips and parent-teacher conferences were tended to by an aunt or a sister or a grandparent. We were the ones the other families whispered about: whose mother had died, whose mother had left with a no-good man, whose mother was lost to the streets or prison or drinking or drugs.

I remember feeling terribly sorry for the kids whose mothers had abandoned them, and terribly afraid I’d be mistaken for one. Because my mother hadn’t ditched me; she was working to save the world from the ravages of capitalism. There was a reason she wasn’t with me. A good reason. The button was my proof. And for years, it was enough.

When I was 3, my mother sent me to Brooklyn to live with her parents. According to family lore, shortly after I arrived, my grandfather, Pop, took me to ride the city bus. We joined a crowd of commuters shuffling their feet at the corner stop. Confused, I asked one of the adults where their signs were. Until then, I’d never seen a gathering of grown-ups who weren’t protesting something.

I’d spent the first years of my life being shuttled from meeting to rally to picket line. Hugo Blanco, who had led an Indigenous-peasant uprising in Peru, was one of my babysitters; so was Fred Halstead, the 6-foot-6-inch anti-war activist. At rallies, especially pro-choice ones, I was a useful prop. See? We don’t hate babies! There I was, on my mother’s hip, a cigarette in her mouth and a stack of flyers in her hand, as she spread the word of the revolution.

In Brooklyn, it was Pop who kept my mother present for me, in addition to overseeing potty training and taking me to dance class. My grandmother was less involved; after working all day in a school cafeteria and fastidiously cleaning our home, she often took to her bed. In those early days, my mother was writing for the Socialist Workers Party’s newspaper, The Militant, and making a lot of trips to Latin America, giving speeches to the proletariat. I knew this because the party videotaped these speeches and my grandfather mail-ordered all of the videos. Although he had voted for Richard Nixon, Pop supported whatever his children pursued. On rainy Saturdays, he would screen my mother’s speeches while I sat cross-legged on the floor, transfixed. In this way, my mother and I had a perfectly lovely relationship as virtual strangers.

Each week, he scanned his copy of The Militant for articles she’d written or references to her. He read to me about how she was advocating for women’s rights in Puerto Rico; next she was in Washington, D.C., speaking about the transit workers’ union negotiations; then she was running for mayor of New York in 1985 on a platform of preserving the city for “working people.” When she wasn’t giving speeches, she was embedded in factories—an auto plant, a bra maker—galvanizing the unions while working the assembly lines. My grandfather would clip out the articles, and I would underline the words and phrases I didn’t know and look them up in our big dictionary: colonialism, collective bargaining, fascism. Concepts that seeped into my consciousness before I had any context for understanding them. These were my mother’s things. These were the reasons she’d left me. And therefore they must be very important.

Once a year, my mother would come to visit for a week around Christmas. Normally my grandparents and I spent our Sundays having dinner with 20 or 30 cousins and great-aunts and -uncles. But when my mother came to town, our family shrank to the four of us. If a cousin or an aunt stopped by for cake and coffee, a tense silence would fall. No one knew what casual bit of conversation my mother might take as a political provocation. There was no wrong time, she seemed to feel, to fight for justice.

She always brought me a doll from the countries where she’d gone to battle the bourgeoisie. The dolls came in shades of brown and black and were made of fabric, with native dresses and elaborate hairdos. They were better than any Barbie or Cabbage Patch Kid, my mom would say, because they were made by hand, not by a corporation; they sprang from tradition, not a marketing department. She told me about the women who made the dolls—how they faced many oppressions but would someday rise up.

During the day, my mother would head into Manhattan and meet up with friends from the party, and I’d play with my new doll at home. At night, she’d chain-smoke and watch TV with my grandparents. But sometimes, during these visits, I’d catch my mother staring at me. “You’re pretty,” she’d say. I’d reply that we looked alike—people were always commenting on how we looked and talked and even moved alike. But inevitably she would say, “No, you’re prettier.” As I got older, this made me uncomfortable. I could plainly see that my mother wasn’t vain. If she was giving me a compliment about something of such little consequence to her, it must be the only thing she could think to say.

After a few days of this, she would leave—go back to a factory or the campaign trail. In my room, my grandfather had built a shelf for the dolls, each under a clear protective dome. When my mother was gone, he’d ascend the stepladder and add the new doll to the others, the task becoming a ceremony that marked her departure. Over the years he expanded the shelf until eventually it wrapped around my bedroom, and the totems of Black and brown women from across the world looked down on me while I slept.

Not long ago, a young author whose work I enjoy invited me to dinner. It was a pleasant enough meal until, over oysters and charred octopus, the author began throwing out socialist jargon—class struggle, oppressors, imperialism—and talking about us, two white-collar writers dining in a lovely restaurant, as “exploited laborers.”

The idea of me—paid a comfortable wage to sit around all day, think thoughts, and type them out—being an “exploited laborer” felt insulting. It was an insult to people like my grandparents, who worked blue-collar jobs all their life. It was an insult to my mother. “What are we risking,” I asked my young companion, “carpal tunnel?”

I had spoken with my mother maybe four times in the past 15 years. But I found myself wondering what she’d make of the conversation. What would she—who’d devoted so much of her life to her ideology—make of the soft lives and hard absolutism of so much of today’s far left?

My mother’s parents grew up in the same tenement building in Red Hook, Brooklyn, during the Great Depression, in the kind of poverty that might have been depicted by a Puerto Rican Charles Dickens. My grandmother and her siblings were orphans—10 of them in a railroad apartment, the eldest still a teenager. Pop’s family lived a floor above and was a little better off—his parents weren’t dead, and he was one of only seven. At 18, he fought in World War II. A year after he came home from Europe, he married my grandmother, and he eventually got a job fixing trains for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

By the spring of 1969, their family was doing well. Their oldest daughter, Linda, a bottle blonde with a German Irish husband, was working as a receptionist at General Electric; my mother, the bookish, black-haired sister, was in her first year at Brooklyn College; and Alberta, the youngest, was 11 and enrolled in Catholic school. Then one day at the train yard, Pop was lying underneath a subway car, repairing a break, when a motorman turned the engine on and began to drive the train forward, dragging Pop along with it.

He was lucky to survive, but one of his legs had been shattered. He was in a cast up to his thigh, trapped in the apartment for months, unable to work. His union and workmen’s comp were the only things that ensured our family’s survival. Just a few months later, while Pop was still laid up in bed, Alberta went to a Mets game and came home complaining of a headache. A week later, she was dead. My grandmother, already prone to depression, was leveled. My mother was radicalized.

Alberta died from encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain linked at the time to mosquito-borne viruses. My mother learned that such illnesses were sometimes traced to poor sanitation in low-income neighborhoods. This opened her eyes to many other unfair things in the world. She was reading Malcolm X and Frantz Fanon, and one day on campus she encountered some people selling copies of The Militant. They, too, saw the injustice of the world. Moreover, they had a theory for how to change it—a vision for a new world order. They were from the Socialist Workers Party.

My mother joined their movement, first as part of the Young Socialist Alliance, and later as a full member. The revolution required devotion. Membership involved many meetings: educational forums on the “Cuban situation,” organizational meetings on anti–Vietnam War efforts, lectures by comrades visiting from abroad, branch meetings, executive meetings, youth meetings, committee meetings. Members were responsible for selling Militant newspapers each week. For a time, The Militant ran a scoreboard that tallied which branches were performing best. Many comrades spent Saturdays hawking books with titles such as Sandinistas Speak and The Housing Question from the group’s publishing imprint, Pathfinder Press. They handed out flyers at factories and joined striking workers to show their solidarity. All of this added up easily to 10 or more commitments a week. Failure to participate could result in expulsion.

The revolution was also nomadic. The party’s ranks were growing—the anti-war movement had brought many young people to the party. New branches needed to be opened, others revitalized. Members were deployed and redeployed by party leadership. A steelworker in a union in Detroit might be sent to live in the South, where a labor grievance was brewing. A year later, he might be ordered to Pittsburgh. The blow of a cross-country move was softened by the fact that you’d always have a place to stay: Party members were expected to open their homes to newcomers. They were glad to do it—and why wouldn’t they be? They weren’t hosting a stranger; they were hosting a comrade they simply hadn’t met yet.

Each August, members from all over the United States, and sometimes from overseas, would descend on the campus of Oberlin College, in Ohio, for the party’s convention. There would be educational sessions on the Russian Revolution and rallies to raise spirits and funds. Comrades would spread out on the lush, green lawns, debating the minutiae of the party’s position on Cuba or Grenada. They shared wine, cigarettes, and often each other’s beds.

That’s where my parents met, in 1975. My mother was working on desegregation in Boston, and would soon move to L.A. to run a new branch office there. My father was handsome and three years her junior. Soon, they were married. And in 1977, I was born.

Here is an incomplete list of the many people who raised me in my mother’s absence: my grandparents. Their brothers and sisters and children. Mister Rogers. The librarians at the Brooklyn Public Library. Maria from Sesame Street. Judy Blume. L. M. Montgomery. Lisa Lisa & Cult Jam. The entire cast of A Different World. Seventeen magazine. Mariah Carey. The women on the Planned Parenthood hotline. My English teacher. My drama teacher. My friends’ moms. Zora Neale Hurston. Kurt Cobain. John Hughes. Every shopgirl at Patricia Field and Ricky’s. All of my high-school boyfriends. F. Scott Fitzgerald. Sandra Cisneros. Lil’ Kim. The streets. The club.

My friends. All of my beautiful friends.

There were others as well, people I was too young to remember but who felt they’d played some role in my upbringing. After my first novel came out, many of these people sent me messages because they had held me on their knee once or had babysat me, and ever since then had wondered, as one woman wrote to me, “what had happened to that bright-eyed little girl.” That woman said she’d thought of me often over the years, but, “for a long time, I was reluctant to ask either of your parents what happened to you, because I thought it might be a sad story.” Old Socialists I’d never heard of sent baby pictures of me; told me that I’d lived with them for weeks or months; had stories about taking care of me, facts I’d never known about my own life. A few described reading to me, claiming some credit for my literary career. And maybe they were right.

My novel Olga Dies Dreaming was not about my mother, but it did borrow the basic premise of our lives. It follows two siblings who were abandoned as children by Blanca, their mother. Blanca is a member of the Young Lords, a Latino civil-rights organization, and she left to pursue the liberation of Puerto Rico. Hurricane Maria, which devastated the island, brings Blanca suddenly back into her children’s lives. And in an indirect way, it brought my mother back into mine.

I wanted Blanca to be historically accurate. Researching the radical movements of the era, I stumbled upon an article in The Militant, from 1984, about my mother. There she was campaigning in Puerto Rico, denouncing the repression of unions and cheering on the independence movement. It was funny—I was over 40, and I’d had access to the internet for half my life, but I had never thought before to use it to piece together my mother’s life.

I found an op-ed she wrote about the need for bilingual education reform: “Memories of my own school days in New York City include teachers telling us ‘to go back to San Juan’ (Puerto Rico) if we didn’t speak English and washing our mouths out with soap for speaking Spanish in class. The message they sent was clear: you, and your language were inferior.” Here was a memory that I could relate to, just not one that I’d ever heard before.

The New York Times featured my mom in an article about the female candidates running for vice president in 1984. Angela Davis, the Communist candidate, thought that the slate of women was fantastic and that everyone should do whatever they could to stop Ronald Reagan. My mother was, to my amusement, less impressed. The Times quoted one of her articles for The Militant : “The Ferraro candidacy is another attempt to convince women and other victims of capitalist society that progress can indeed be won through the two-party system.” The article then mentions that my mother was from Brooklyn, Geraldine Ferraro from Queens, to which my mother was sure to add that the differences between them were “more than just boroughs.”

I looked further back in time, and read about a press conference she gave denouncing President Gerald Ford’s proposal to make Puerto Rico a state: “Puerto Rico is a colony of the United States. This move is just an attempt to cover up the colonial status and to continue to make profits.” She popped up year after year, like the Forrest Gump of socialism. The date at the top of the article was the only proof that she was, at that moment, newly pregnant with me.

By the time I wrote Olga Dies Dreaming, I’d achieved quite a bit of healthy peace around our estranged relationship. Still, when I found a small mention in the Times, from 1984, about her vice-presidential run that said she was living in New Jersey, I was shocked. The whole year I was 6, she’d been right across the river, and all I could remember clearly was her Christmas visit.

Worse was a story about her candidacy for mayor of New York, when she ran against Ed Koch. That placed her even closer—in New York City, when I was 7 and 8. I had somehow never thought about this before: Of course one needs to reside in a city in order to run for mayor of it. All that time I was wearing her campaign button, she was only a subway ride away.

When I was about 13, my mother didn’t come back to Brooklyn for her Christmas visit. She’d been playing Norma Rae on an automobile assembly line in St. Louis when she met a Vietnam vet who had two small children—a girl and a boy, then 3 and 4. That year, my grandmother informed me, my mother was going to stay in Missouri and have Christmas with him.

In the summer, it was suggested that I go out to visit her—something I’d rarely done—and meet her boyfriend. They were living with his children and planning to get married. In all the talk about her new life, I noticed that we no longer discussed her work with the party—no one mentioned any speeches, or campaigns, or trips abroad. She had retired, apparently, given it all up, and no one said a thing about it. All I knew was that where there had once been sparse furnishings and perpetual calls to offer new addresses, she now had a new family and a big home with a “great room.” They raised dogs, including one that was allegedly 86 percent wolf. At the wedding, there was country line dancing. After, a Costco membership. Her days of activism were over.

My grandfather was shocked, my grandmother bemused. I quietly seethed. Socialism had been my mother’s religion, and my mother had been mine. Now none of it mattered. I declared myself too old for dolls and packed my watchwomen into a box.

After my mother settled down in the Midwest, our relationship got both more intimate and more estranged in unpredictable turns. It was my mother, for instance, who taught me to use a tampon during a summer visit to St. Louis, when her husband—a totally lovely man—insisted on taking us camping. We were going to swim in the river, and when I complained that I had my period, my mother handed me a Tampax. “Grandma said virgins can’t use these,” I remember saying. “Grandma also thinks men have less ribs than women and that’s not true either,” my mother said, as she gently shoved me into a campground stall. (My grandmother, for what it’s worth, did believe this—because of Adam and Eve—and could not be convinced otherwise.)

I remember eating dinner with them outside as a storm came over the plains. “That’s what weather looks like,” her husband said. It was big and wild and interesting. And I saw how it must feel that way to my mother too—so different from the cramped skyline back home.

But then I would see her with his children and it would fill me with rage. Or she would take the mother act too far and try to weigh in on my studies or whom I was dating. We would spend a week together, erupt into an argument, and not speak again for months.

Once, before their wedding, when I was about 15, I was sent for a visit and we went on another camping trip. The little kids wouldn’t come, my mother promised me. Instead it was just me and her and her fiancé and a young relative of his. I guess it never occurred to the adults that us sharing a tent might be a bad idea. That night, the boy’s aggressions sent me silently running from the tent. I hid in the campground bathroom, empty save for a stray dog and a scapular, a Catholic devotional necklace made of fabric, hanging from the mirror. I woke in the morning with the dog curled beside me and the scapular in my hand, and I walked back to our campsite. Save for two postcards I sent to friends back home, I have never said anything about that night until now.

In my mother’s absence, I looked for meaning in all the things that were not hers. As a high schooler, I tried on Republicanism, but then Republicans gave us Clarence Thomas and Rush Limbaugh, and even as a teenager, I couldn’t get down with that. Instead, I embraced stories of meritocracy and individualism—of people who made a life for themselves without following in anyone’s footsteps. I worshipped Jim Morrison and obsessed over The Fountainhead ’s Howard Roark. Oprah was my idol. Bill Clinton was my role model. My mother was appalled, but I saw that he was like me: someone with no one around to help him except the good teachers who saw just how special and smart he was.

When I got into Brown, my mother was no more approving. She thought that an Ivy League education was a waste of money, the schools just a breeding ground for snobbery. But I was learning things. Money, until then, had existed in degrees of scarcity. Rich was a relative term, one bestowed in regard to the number of Jordans someone owned or whether their parents could afford to buy them a car. At Brown, I discovered that real wealth was something else. It was access: to culture, to experiences, to power. I believed that with enough hard work, those things would all come my way.

My memory of my college graduation is marred by a fight my mother picked with her older sister at dinner. My aunt Linda, an English teacher, had been the one to drive me around on college tours and proofread my papers. I’d sent her my senior thesis to read, and it had won a departmental prize that was awarded during the ceremony. But the topic—colonialism and Postimpressionistic painting—irritated my mother. She hadn’t read the paper, but I remember her railing against it anyway. Something about artists making decorations for the moneyed class. Aunt Linda defended my paper. My mother proclaimed her an out-of-touch member of the petite bourgeoisie. I recall a glass of wine being thrown. Or maybe it was just spilled and I have watched too many telenovelas. Either way, my mother stormed out of the restaurant, and my grandparents ran after her.

In my 20s, my mother and I were distant acquaintances. Unconsciously or not, I ended up in a career that I knew she would despise: planning weddings for the very rich. When Pop died, in 2009, my mother swept in. She gave the eulogy, and in it she memorialized all the things her father had done for her: taught her to read, to write, to be independent, to fix a car. All the things he’d done for her, that is, with one exception—raising me. And that omission was the one thing I could never forgive.

This spring, my mother and I had our first real conversation in years. Outside of family funerals, we’d rarely talked; I didn’t even have her phone number. We spoke on Zoom, which she hadn’t used before, and when she finally got the camera working, I could see a wood-framed landscape painting hanging over her head, the kind you might find at HomeGoods. Her lifestyle had changed, but her politics had not. When I asked about her position today, she told me, without hesitation, “I still do believe totally in the power and the capacity of the working class on a world scale to bring about a just world.”

After she left the party, she continued working in the Missouri factory she’d been deployed to. For two decades, until the plant closed, she installed fenders on minivans. She enjoyed the work; she says the auto industry attracts freethinkers. Despite those years in the Midwest, her Brooklyn accent is still so thick that the transcription service I used could barely understand her. At one point, she paused in order to gather her thoughts without using “words that have come to mean nothing.” I could see what so many comrades had admired about her. She is pragmatic on one hand and uncompromising on the other. (She described the left’s beloved Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez as “a very smart young woman” who “does not really advance the self-confidence, self-consciousness, or the organization of working people. Because she is a Democrat.”)

But when I tried to talk about personal matters, the conversation foundered. Only through politics could we seem to access each other as humans. The few memories my mother shared about me as a child were almost always anecdotes from her political life, tales more about my absence than my presence.

I showed up in a story about a labor rally in D.C., where my mother was passing out flyers in support of making Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday a federal holiday. Some white men took offense, started to rough her up a bit, and grabbed her bag. She yelled at them: “My kid’s pictures are in there!” They gave the bag back, and she showed them the photos. It helped them realize, she said, that “you may have ideas different from them, but you’re still a human being with kids.” And then, without skipping a beat, “So yeah, we were really trying to convince working people that the way we live now is not the beginning and end of the way we could live.”

We discussed her run for mayor. She said she used to joke that our family was so big, she could come in second with their support alone. That campaign, she said, “was more fun because I was home.” I should have said, “You were home—why didn’t you come see your daughter?” But I didn’t. Perhaps I didn’t want to hear the answer.

When I did finally ask if she regretted not raising me, she answered my question with a story. Two comrades were having a baby and considering giving it up. Someone said that they should talk to her. “I said, ‘Are you outta your mind? Don’t do what I did. That was terrible. That was a stupid thing … Don’t do anything that I did. Don’t do that.’ ”

She told me she had missed the “pleasure of watching you grow and change.” At that moment, I felt sad for her. I felt the need to comfort her. I told her how proud I was of her. I told her about the button. My mother changed the subject.

There’s a kind of powerful woman who can make every member of a crowd feel like the only person in the room, but meet her one-on-one, and you barely register. I’d always seen this as a flaw until I sat down to write the Blanca character in my novel, and recognized it as something else. In a letter about the father of her children, Blanca writes, “I could spend my time soothing his loneliness and hurt, trying to motivate him back into purpose, or I could spend my time working towards the liberation of oppressed people around the world. Both, you must understand, are expressions of love.”

To my surprise, my mother told me she liked the book, and when I asked if she saw herself in Blanca, she said, “Oh, very clearly.” Then she said that the novel had made her consider, for the first time, how her absence had made me feel: “I know how I looked at things, and the book made me think, ‘Well, this is how you saw things.’ ” She thought at the time that she was doing the right thing: “Okay, this is the best situation I can create given my situation.” Now she realized that to me, “it had to have felt the other way, like I was dumping you.” She wasn’t apologizing or trying to win me over; her tone was completely matter-of-fact.

The conversation knocked the air out of me. I’d spent a lifetime trying to understand my mother’s experiences, and she had never bothered doing anything of the kind for me.

In her telling, my father was a good person, but he drank and was no help. One day, when I was a few months old, she said she came home from work to find the door bolted from the inside. She could hear me crying, but no one would answer. Eventually she broke in and found my father passed out in a chair and me lying on the floor, covered in urine. “You were soaked to the gills,” she said. The next morning, she told him he had three months to pull it together. (My father, now long sober, denied this account. He always believed she’d left him for another man. My mother said, “I left him because I wanted to be sane.”)

She was a single mother on a working wage, effectively doing three jobs: She had a gig at a factory, she spent her breaks trying to recruit her colleagues to the cause, and she devoted her evenings to party or union work. The party—while empathetic to workers at large—was often insensitive to the individual needs of female comrades. (When the “problem” of women breastfeeding during meetings arose, for example, leadership decided that it was a nonissue: Babies were not full members of the party and therefore should not be at meetings in the first place.)

But also, my mother had been a star. The man she dated after my dad, a fellow comrade named Dave Paparello, told me that she “was a fucking natural.” She wasn’t pretentious or faux folksy, and she had a knack for getting people to listen to her. She could also be, he said, very intimidating. Mel Mason, the former Black Panther who was her presidential running mate, told me that meeting her was “one of the high points of being in the Socialist Workers Party.” She was “a real revolutionary.” But motherhood changed the way people saw her.

I could feel the anger in her voice, all these years later, as she recounted traveling with me from Houston to Dallas to attend a class led by a visiting senior party member, an older man. During his talk, she told me, “you were making a little noise, but you were not crying. You were very well-behaved.” In front of the entire room, the man said, “You have to shut her up or leave.” And so she left.

It wasn’t the last time she would be thrown out of a meeting for bringing her baby. It bruised her ego, but it also bruised her perception of the party’s leadership. She was out there trying to recruit working women from the factory lines, and the party seemed clueless about what life was really like for them.

I asked my mother if she had felt overwhelmed by motherhood, and she admitted that she had. Changing the world, for some of us, feels easier than raising a child. They are both, I suppose, expressions of love.

I’ll probably never fully understand why my mother left the party—it was the one subject related to her career that she was reluctant to discuss. But by the time she resigned, many others had done the same thing. The late ’80s and ’90s were a period of decline. The exodus was a response, in part, to the exhaustion from civil-rights battles fought and won, and to the end of the Vietnam War. But for many members, the problem was not a loss of faith in the cause, but frustration with the autocratic nature of party leadership. Just as members felt they were making progress in a posting, they might be told to leave. Anyone who questioned their assignment was assured that someone else would be sent to take their place, as if they were all interchangeable.

Dave Paparello had been a member of the party since he was a teenager, but he quit around the same time as my mother. He said the intellectual openness that had drawn him to the party started to “degenerate” and leadership became more “corporate.” Meetings became less about strikes and actions and more about internal party affairs. “Trials,” once rare disciplinary events, became more frequent. The threat of expulsion loomed.

Diana Cantú, a former comrade who briefly dated my father, has kept in touch with me over the years. She majored in medieval studies and worked as a publicist for the Gilbert & Sullivan Repertory Company before she joined the party, learned to solder, and took a job at an electronics plant—mortifying her bourgeois family. She told me that her last days in the party felt like being on one of those centrifugal-force rides at an amusement park, or on a spinning wheel at a playground. Everything went round and round, faster and faster, until people couldn’t hold on anymore. “You see them fly off. And I remember that sensation … You just fly off.”

All of this made sense to me. But none of it explained St. Louis, the Costco membership, and the stepkids. None of it explained how, after decades of radical independence, my mother had seemingly changed her whole life for the love of a man. Talking about my mom, Dave said he just couldn’t “make the puzzle pieces fit.” And that’s true for me too.

I felt betrayed when she left the party, but even more aggrieved that she had raised these two other kids. “I wouldn’t blame you for that,” she told me, during another call. But she insisted that she’d married her husband, “not the kids.” Living with two small children … “I didn’t really care much for doing that, to be totally honest. I thought I wasn’t really good at it.” Sometimes, she said, the kids would give her a hard time, telling her, “You’re not my mother.” And she would say that was right: “ ‘That’s why I don’t love you unconditionally. I don’t love you no matter what you do. Sometimes, I don’t love you.’ ”

In theory—as a matter of policy—my mother did love children. I recently came across a decades-old article about her running for a school-board seat in D.C. that seemed to sum her up. The Washington Post reported that she had been “involved in a program to increase parent involvement in the New York City school system before coming to Washington,” and was pushing for the D.C. board to “more actively involve parents in policy-making decisions.” This was in 1981. Back in Brooklyn, I would have been starting kindergarten.

In the past few years, support for labor movements has been ticking up. Some people compared this spring’s college encampments demanding divestment from Israel to the protest movements of the 1960s. Online, people throw around the word socialism, though many have only the vaguest grasp of what the ideology entails. Much of the far left’s energy seems more focused on rhetoric than on real work. It’s hard to imagine those college students, for example, packing up their tents and pulling a swing shift at a bra factory.

But one thing feels similar, and that’s the absolutism required to be “down for the cause.” The righteousness of the collective pursuit serves as justification for all kinds of callousness. Dissent, or even nuance, is unwelcome. And nothing is too precious to sacrifice to the cause.

I grew out of my rebellious politics a long time ago. On most issues, my mother and I are aligned. I’m a member of two unions, including the Writers Guild of America, and I supported our strike last year. But life imbued me with a journalist’s skepticism of all brands of certainty. I’ve seen too much of movements to trust them. Protests give me claustrophobia. Rallies cause heart palpitations. Honestly, even stadium concerts make me uncomfortable. Collective power moves me; collective thought freaks me out.

The Socialist Workers Party still exists, but its ranks have dwindled, though my father is still a supporter. Some of its positions—for example, its staunch support of Israel (the party argues that Iran, not Israel, is the main aggressor in the Middle East)—have left it out of step with many on the left. The most influential socialist party in the U.S. now is probably the Party for Socialism and Liberation. It’s running two Latina candidates for president and vice president this year, Claudia De la Cruz and Karina Garcia. They agreed to an interview with me. They are passionate and eloquent and—not that it matters—beautiful. I thought I detected some mild disdain from one of the women over having to engage with such a centrist mainstream-media hack as myself. (My politics are far more Elizabeth Warren than Trotsky.) I was not offended; I was relieved. This woman knew that my struggle was not the home attendant’s struggle or the minimum-wage worker’s struggle. When I asked what their goals were, they said: Burn it all down. Start from scratch.

I agreed with many things that they said: Our democracy was structured to protect capitalism and disenfranchise labor. The two-party system is broken, and we are absolutely living under the whims of a billionaire class. But when they talked—with radiant clarity—about the need to sublimate the individual to the collective in order to create true change, I bristled.

When my mother told me she hadn’t ever considered how I felt about growing up without her, my first reaction was that her wiring was off. But speaking with those two Socialist candidates, I came to view it differently. All around my mother, people were being told to give up one life here and start another there. And they did, no questions asked. She must have seen me as just another comrade being relocated for the movement. She had not considered my feelings because, I suspect, she had not considered her own.

The happiest my mother sounded during our calls was when she was talking about the successful organized-labor actions that took place last year—strikes by health-care workers, United Auto Workers, the Screen Actors Guild. “I love that guy!” my mother said about Chris Smalls, the Amazon Labor Union leader from Staten Island. “I love him, right, where he wore his leather jacket and his cap. I thought: This is what union organizing should look like. Everyday people.”

She sounded like a proud parent.

This article appears in the September 2024 print edition with the headline “My Mother the Revolutionary.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.