Shopping

What the Potential Pedestrianization of Europe’s Busiest Shopping Street Can Teach U.S. Cities — Streetsblog USA

It’s a familiar story to transport policy watchers around the world: different types of road users locked in a fierce competition for the street. Recent Streetsblog posts have, for instance, discussed the car traffic slowing down buses in the Bronx, and the vehicles illegally parking in bike lanes throughout Chicago.

Where people want to use the same roadspace for different purposes, there are always going to be winners and losers in any changes policy-makers attempt to make. Where the political control of a street is also contested, problems can be even harder to solve.

The recent history of Oxford Street in London, England provides an object lesson for US cities in the difficulties in resolving these long-standing issues.

Oxford Street is the premier retail destination in London. Among the 300 stores along its 1.2 miles are flagship outlets for major national and international brands such as Selfridges, John Lewis, H&M, Disney, Nike, Gap and Adidas. Half a million people visit the street every day.

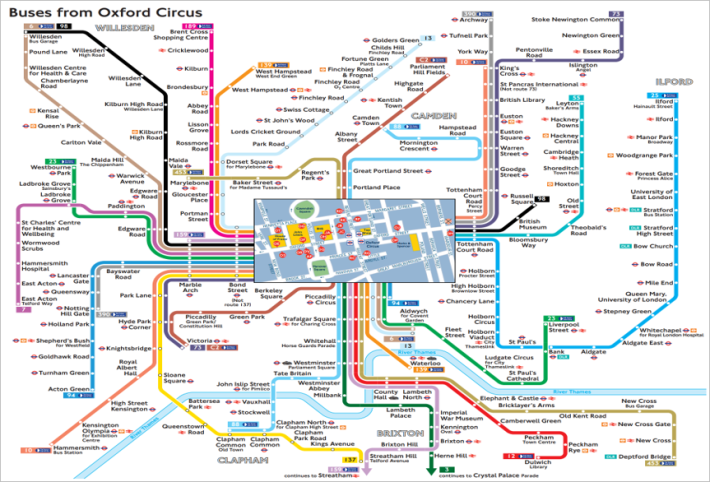

However, the location of the street means it also serves as one of London’s most important transit routes, especially for buses. This part of central London — the West End — is home to London’s theater district and some of the city’s wealthiest residents, as well as a densely packed web of disordered streets. Moreover, Oxford Street is a historic route linking London to the west coast of Great Britain and, to the inconvenience of its retailers, is one of the only major east-west thoroughfares that can be used to traverse the West End. The volume of traffic any given time is huge, and the space available for it is very limited.

Private cars are restricted from Oxford Street during the day, with the traffic comprising buses and taxis, as well as cyclists willing to brave the jams. Sixteen bus routes serve Oxford Street, arriving from every corner of the city. One former Mayor of London, Boris Johnson, said that Oxford Street was, “bisected by a panting wall of red metal,” referring to the distinctive color of London’s double-decker buses.

A useful comparison can be drawn with the Avenue des Champs-Élysées in Paris, France, which is almost exactly the same length as Oxford Street. While ostensibly performing similar functions within their cities as retail centers, transit routes, and tourist attractions, the difference between the street environments is clear. The Champs-Élysées is a tree-lined boulevard with multiple lanes of traffic in each direction and spacious sidewalks – which is not to say it does not have its own issues, which Paris Mayor Ann Hidalgo is seeking to address.

Oxford Street has problems with severe pedestrian overcrowding on its narrow sidewalks, making the street particularly challenging for visitors with mobility issues. On the road, the buses from those many routes can be found queuing bumper to bumper for much of the day, inching slowly along just one lane of traffic in each direction. Collisions are common: over the past eight years, a serious injury has occurred more than once a month on Oxford Street, on average, with four fatalities in this period.

Still, Oxford Street remains a desirable destination for its many shoppers, and a prestige location for retailers. But the street environment means that many will not find it a pleasant experience to visit, and there are concerns that this is affecting its economic success. Growing competition from online retail and large malls outside central London exacerbate these concerns. Local policy-makers and businesses have spent much of the past two decades seeking ways to improve the environment, with some successes, but without yet bringing about any fundamental transformation.

Three mayors, three visions for Oxford Street

Successive Mayors of London have attempted to solve the Oxford Street problem.

London’s first directly-elected Mayor, Ken Livingstone, proposed a new light rail system, known as the Oxford Street Tram, in 2004. Greater London has two light rail networks, in the south and east of the city, in addition to its London Underground rapid transit network and other heavy rail networks covering the entire conurbation. Mayor Livingstone’s proposal was for a limited-scope service, with a streetcar running back and forth along Oxford Street only. It would have supplanted the bus routes, which would have been removed. Later, Mayor Livingstone’s ideas evolved into a shuttle bus service instead of light rail, although in essence the proposal was the same.

Mayor Livingstone himself noted the logistical problems with the proposal. The most difficult of these was what to do with the buses and their passengers. As buses would still be running to and from the ends of Oxford Street, there would need to be new, large interchange facilities at either end to allow passengers to switch from bus to streetcar (or from regular bus to shuttle bus), and possibly back again at the other end. Another aspect of the light rail proposal was that while it may have improved the pedestrian environment on Oxford Street by virtue of removing motor traffic, it would not have given pedestrians more space than they already had.

When Boris Johnson replaced Ken Livingtone as Mayor in 2008, one of his first acts was to cancel the development of the light rail/shuttle bus proposal, on cost grounds. Mayor Johnson did, however, accept the need to improve the Oxford Street environment. Under his leadership, the city’s strategic transport authority, Transport for London, cooperated with partners on public realm enhancements, and reduced the number of bus routes serving Oxford Street in order to alleviate congestion somewhat.

Oxford Street was still considered a significant problem for the city, however, by the time Sadiq Khan succeeded Boris Johnson as Mayor in 2016. Mayor Khan’s proposed solution was more radical than those of his predecessors: full pedestrianization of Oxford Street. This was not an entirely new idea, as it had been proposed in different forms in reports by the London Assembly – the body elected to scrutinize the Mayor – in 2010 and 2014, but had not been adopted before as mayoral policy.

In addition to the logistical issues that would need to be addressed, the pedestrianization proposal for Oxford Street had to take into account the complex arrangements for ownership and management of London’s road network.

The vast majority of roads in London are owned and managed by London’s 32 boroughs. The Mayor of London, via control of Transport for London, owns and manages five percent of the network, primarily strategic roads known as ‘red routes’. Despite its strategic importance, Oxford Street is not a red route; rather, it is controlled by the local borough, the City of Westminster.

This means that any transformation of Oxford Street would ordinarily depend on agreement between the Mayor and Westminster City Council. Initially, Westminster did support the Mayor’s pedestrianization proposal in 2016, but in 2018 it withdrew its support. It appeared this was driven by opposition from local residents in the surrounding area, concerned by the prospect of traffic, especially buses, being displaced onto residential streets.

The future

Six years later, with Mayor Khan re-elected for a third term in office, the pedestrianization proposals have again been brought forward. The key difference in the new proposals is that Mayor Khan is proposing a change in the political oversight of Oxford Street.

Firstly, this would involve transferring Oxford Street from borough control to Mayoral control, making it a red route, under a little-used provision of the legislation that established Mayoralty and its powers (Section 261 of the Greater London Authority Act 1999). This would give Transport for London the power to restrict traffic from using the street as required. Ordinarily, the City of Westminster could block this transfer of authority, but the law allows for borough objections to be overruled by the UK Government. After the recent UK General Election was won by the Labour Party, to which Mayor Khan also belongs, it now appears likely that he would have Government support for this move.

The second change would be the establishment of a Mayoral Development Corporation for Oxford Street. Using powers under different legislation (the Localism Act 2011), the Mayor of London is able to designate an area of the city as a Mayoral development area, for the purposes of regenerating it. This also involves the Mayor assuming powers that would otherwise be held by local boroughs, this time over planning (analogous to zoning powers in the United States). The Mayor would then effectively control what development can and cannot take place in and around Oxford Street. Previously, this power has been reserved for areas of industrial land that have the potential for significant new housing and other development.

The implications of Oxford Street pedestrianization are complex and need very careful consideration. Buses that many Londoners depend on will need to be diverted elsewhere, or curtailed in their routes. Cyclists will not be able to use Oxford Street once it is pedestrianized, and will want other, safer routes to be made available to allow them to travel across Central London. The competition for space in this part of the city is not yet at an end, but is about to enter a compelling new phase.

Editor’s note: This post reflects the findings of the London Assembly Research Unit‘s report Pedestrianising Oxford Street. It does not represent a statement of policy on behalf of the Mayor or the Assembly.

.jpeg)