World

When the End of Humanity Isn’t the End of the World

During the early months of the coronavirus pandemic, when many countries were enacting variations of lockdown protocols, air pollution and greenhouse-gas emissions decreased drastically. A meme began to spread across social media proclaiming that, with so many people spending most of their time at home, nature was healing. Images of clear canals, clean skies, and wild animals roaming empty city streets were accompanied by the phrase “We are the virus.” The memes quickly turned silly, and their core claims were roundly debunked as overly simplistic, plain wrong, and somewhat eugenicist. Beyond all this, the trend was deeply ironic: By diagnosing themselves as a pox upon the Earth, people were revealing their degree of self-obsession—a belief that humanity is so powerful and important that the briefest pause in our normal activities would have meaningful consequences for the planet.

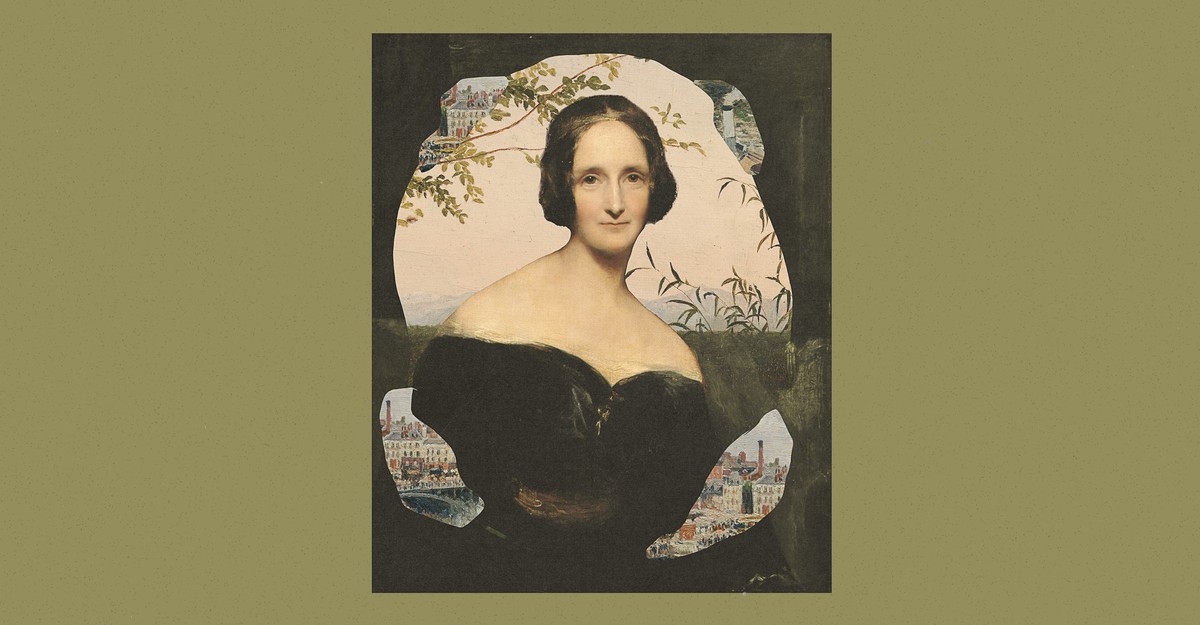

Nearly two centuries ago, the English author Mary Shelley confronted human beings’ instinctive anthropocentrism in her 1826 novel, The Last Man, which was published eight years after Frankenstein and has recently been reissued. Even then, Shelley might already have been thinking about humanity’s impact on Earth: As the scholar John Havard writes in his introduction to this new edition of the novel, at the time of her writing, “England was already responsible for most of the world’s carbon emissions. The wheels were in motion for the kind of Promethean unleashing of fire that created today’s climate change.”

The Last Man is narrated by an Englishman named Lionel Verney, and takes place from 2073 to 2100, during which time he witnesses the beginning, middle, and end of a pandemic so deadly it appears to kill every single human on Earth except for him. Shelley’s wasn’t the first literary work to explore the notion of a lone survivor of an apocalypse; she was preceded even in her own century by Jean-Baptiste Cousin de Grainville’s novel, Le Dernier Homme, as well as by poems by Lord Byron and Thomas Campbell. But rather than viewing the end of mankind as the end of the world, Shelley examines the extinction of humanity on an Earth that keeps on living.

Shelley’s novel is preoccupied with how unnecessary human beings are to the planet’s continued revolution around the sun—its changing seasons, the survival of its other inhabitants. As the plague wipes out large swathes of the population, Verney mourns the loss of human relationships and creativity, but also recognizes that nature is full of its own unique bonds, rhythms, and beauty. Ultimately, The Last Man seems to celebrate the notion of life itself as worthy, whatever form it takes. Of course, we should attempt to reverse the damage we’ve wrought on the planet. But it might also behoove us to practice humility in the face of nature’s awesome forces.

Shelley’s narrator has a unique relationship to the nonhuman world. His parents died when he was a child, and he was raised as a shepherd in service to a farmer in Cumberland. There, he grew up wild, “rough as the elements, and unlearned as the animals [he] tended.”

Verney’s life changes suddenly as a teenager, when the English king’s son, Adrian, visits Cumberland. Verney’s late father had been friends with the king, and recognizing their shared history, Adrian lifts Verney up into the rarified world of the peerage. He invites the boy to live and travel alongside him, and under Adrian’s tutelage and with his resources, Verney studies poetry, philosophy, and science. Yet Shelley makes clear that Verney had never been ignorant: Having spent much of his youth laboring outdoors, he was deeply knowledgeable about “the panorama of nature, the change of seasons, and the various appearances of heaven and earth.” Given the years Shelley spent among some of the foremost Romanticists, including her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and their close friend Lord Byron, it isn’t surprising that her protagonist finds, in the natural world, plenty to enrich the mind and spark curiosity.

Part one of the novel is primarily concerned with conveying the richness of Verney’s social and political life, which is to say, the importance of his human relationships. But Verney’s narration also makes heavy use of natural metaphors and lengthy descriptions of landscapes; in one scene, for instance, he describes the love of his life, Idris, as a “star, set in single splendour in the dim anadem of balmy evening.” Shelley seems keen on demonstrating that despite the comfortable life of the mind Verney now lives, he never loses his reverence for nature.

In the novel’s second part, the plague—an airborne virus with no clear pattern of contagion—makes its first appearance amid a Greek war of independence from the Ottoman empire. Beginning in Asia and spreading globally, the plague ends up turning the tide of the war as the residents of a besieged Constantinople fall ill and die quickly. One of the novel’s major characters, Lord Raymond, who is married to Verney’s sister, had traveled to the empire’s capital to join the war effort on the side of the Greeks; Verney and his cohort, including his sister, his wife, and Adrian, accompanied him there. Soon after, the plague strikes, and Verney and his circle retreat back to England, where they believe they will be safe from the disease. Before long, though, the plague arrives on England’s shores, ravaging the population.

Verney’s contingent survives the worst of the plague and soon leaves England in search of a climate less friendly to the disease. When they arrive in France, they find that their fellow survivors have broken into groups, including one whose extremist religious leader insists that humanity’s sinfulness is to blame for the plague’s spread. This section includes some of the novel’s most rapturous meditations on the natural world’s continued survival amid mass human death. Verney wanders among winter-stricken towns in whose buildings both wild and once-domesticated animals find shelter; watches as nature presents “her most unrivalled beauties” in lakes and mountains and enormous vistas; and, “carried away by wonder,” forgets about “the death of man.” As more and more humans disappear from the Earth, Verney and his companions are left to find solace in the planet’s ongoing cycles and the life that still inhabits it.

By the end of the novel, Verney’s entire family and his closest friends have perished. Somewhat bitterly, he watches the thriving flora and fauna around him. But instead of cursing nature’s survival even as his species is going extinct, he recognizes the similarity between himself and the nonhuman animals who keep living: “I am not much unlike to you,” he proclaims. “Nerves, pulse, brain, joint, and flesh, of such am I composed, and ye are organized by the same laws.” Even the last man, as he believes himself to be, cannot begrudge the continued turning of the Earth and the flourishing of its creatures. The Last Man is only one radical guess at a potential future, but in it Shelley reminds her readers that humans need Earth far more than Earth needs us.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.