Tech

Why is this Chinese video game causing such a stir?

Getty Images

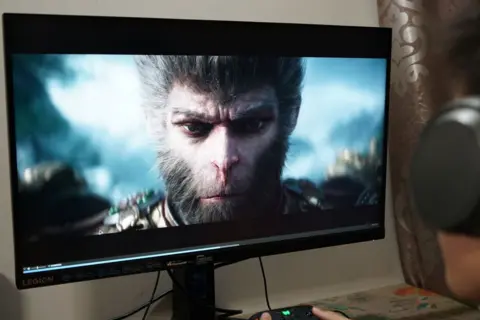

Getty ImagesAn anthropomorphic monkey and a campaign against “feminist propaganda” set the video gaming community alight this week, following the release of the most successful Chinese title of all time.

Many players were furious after the company behind Black Myth: Wukong sent them a list of topics to avoid while livestreaming the game, including “feminist propaganda, fetishisation, and other content that instigates negative discourse”.

Still, within 24 hours of its release on Tuesday, it became the second most-played game ever on streaming platform Steam, garnering more than 2.1 million concurrent players and selling more than 4.5 million copies.

The game, based on the classic 16th-century Chinese novel Journey to the West, is being seen as a rare example of popular media broadcasting Chinese stories on an international stage.

What is Black Myth about?

Black Myth: Wukong is a single-player action game where players take on the role of “the Destined One”- an anthropomorphic monkey with supernatural powers.

The Destined One is based on the character of Sun Wukong, or the Monkey King, a key character in Journey to the West.

That novel, considered one of the greats of Chinese literature, draws heavily from Chinese mythology as well as Confucianism, Taoist and Buddhist folklore.

It has inspired hundreds of international films, TV shows and cartoons, including the popular Japanese anime series Dragon Ball Z and the 2008 Chinese-American fantasy film The Forbidden Kingdom.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhy is Black Myth such a huge hit?

First announced via a hugely popular teaser trailer in August 2020, Black Myth launched on Tuesday after four years of anticipation.

It is the Chinese video game industry’s first AAA release – a title typically given to big-budget games from major companies.

High-end graphics, sophisticated game design and hot-blooded hype have all contributed to its success – as well as the size of China’s gaming community, which is the largest in the world.

“It’s not just a Chinese game targeting the Chinese market or the Chinese-speaking world,” Haiqing Yu, a professor at Australia’s RMIT University, whose research specialises in the sociopolitical and economic impact of China’s digital media, told the BBC.

“Players all over the world [are playing] a game that has a Chinese cultural factor.”

This has become a huge source of national pride in the country.

The Department of Culture and Tourism in Shanxi Province, an area that includes many locations and set pieces featured in the game, released a video on Tuesday that showcased the real-world attractions, triggering a surge in tourism dubbed “Wukong Travel”.

Videos posted on TikTok in the wake of Black Myth’s release show tourists flooding temples and shrines featured in the game, in what one X user characterised as a “successful example of cultural rediscovery”.

Niko Partners, a company that researches and analyses video games markets and consumers in Asia, similarly pointed out that Black Myth “helps showcase Chinese mythology, traditions, culture and real-life locations in China to the world”.

Why has it sparked controversy?

Ahead of Black Myth’s release, some content creators and streamers revealed that a company affiliated with its developer had sent them a list of topics to avoid talking about while livestreaming the game: including “feminist propaganda, fetishisation, and other content that instigates negative discourse”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile it is not clear what was precisely meant by “feminist propaganda”, a widely circulated report by video game publication IGN in November alleged a history of sexist and inappropriate behaviour from employees of Game Science, the studio behind Black Myth.

Other topics designated as “Don’ts” in the document, which has been widely shared on social media and YouTube, included politics, Covid-19, and China’s video game industry policies.

The directive, which was sent out by co-publisher Hero Games, has stoked controversy outside China.

Multiple content creators refused to review the game, claiming its developers were trying to censor discussion and stifle freedom of speech.

Others chose to directly defy the warnings.

One creator with the username Moonmoon launched a Twitch stream of Black Myth titled “Covid-19 Isolation Taiwan (Is a Real Country) Feminism Propaganda”. Another streamer, Rui Zhong, discussed China’s one-child policy on camera while playing the game.

On Thursday, Chinese social media platform Weibo banned 138 users who were deemed to be violating its guidelines when discussing Black Myth.

According to an article on the state-run Global Times news site, a number of the banned Weibo users were “deviating from discussing the game itself but instead using it as a platform for spreading ‘gender opposition,’ ‘personal attacks’, and other irrational comments”.

Has this affected the game’s success?

While the controversy has attracted a lot of attention in international media and online, it has not really dented or detracted from Black Myth’s overwhelmingly positive reception.

The game made $53m in presales alone, with another 4.5 million copies sold within 24 hours of its release. Within the same timeframe it broke the record for the most-played single-player title ever released on Steam.

On platforms like Weibo, Reddit and YouTube, and elsewhere, reams of comments are celebrating the game’s success. Many suggest that the fallout from the controversies surrounding the game’s release has been overblown.

Ms Yu agreed, describing Black Myth as an “industry and overall market success”.

“When it comes to Chinese digital media and communication platforms, of course people cannot avoid talking about censorship,” she said. “Black Myth is… an example of how to tell the Chinese story well, and how to expand Chinese cultural influence globally. I don’t see any censorship there.”

She also pointed out that apparent attempts to steer or censor what reviewers said were unlikely to have come from Chinese officials themselves. More likely, Ms Yu suggested, is that the list of “Dos” and “Don’ts” came from a company that was trying to keep itself out of trouble.

“The company issues their notification so if anybody from the central government comes to have a chat with the company, the company can say, ‘look, I already told them. I can’t stop people from saying what they want to say.’

“They have basically, to use the colloquial term, covered their own ass,” she concluded. “I view it as a politically correct gesture to the Chinese censors, rather than a real directive coming from the top down.”