World

Why rising Arctic wildfires are a bad news for the world

Smoke from raging wildfires has once again darkened the skies over the Arctic. It is the third time in the past five years that high intensity fires have erupted in the region, Europe’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) said last week. A majority of fires are in Sakha, Russia, where more than 160 wildfires charred nearly 460,000 hectares of land up until June 24, according to Russia state news agency Tass.

The June monthly total carbon emissions from the wildfires are the third highest of the past two decades, at 6.8 megatonnes of carbon, behind June 2020 and 2019, which recorded 16.3 and 13.8 megatonnes of carbon respectively, C3S added.

Wildfires have been a natural part of the Arctic’s boreal forest or snow forest and tundra (treeless regions) ecosystems. However, in recent years, their frequency and scale in the regions have increased, primarily due to global warming. More worryingly, these blazing wildfires are fueling the climate crisis.

Here is a look at why Arctic wildfires have become worse over the years, and how they are exacerbating global warming.

Why have Arctic wildfires become worse?

The Arctic has been warming roughly four times as fast as the world. While the global average temperature has increased by at least 1.1 degree Celsius above the pre-industrial levels, the Arctic has become on average around 3 degree warmer than it was in 1980.

This fast paced warming has led to more frequent lightning in the Arctic, which has further increased the likelihood of wildfires — lightning-sparked fires have more than doubled in Alaska and the Northwest Territories since 1975, according to a 2017 study.

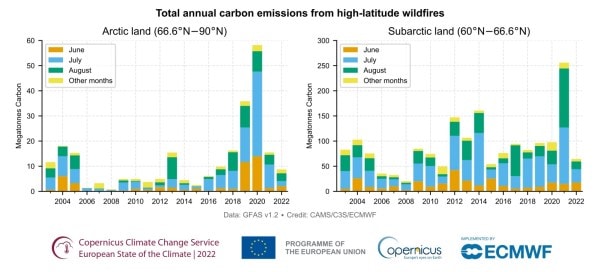

Annual total estimated carbon emissions (megatonnes) from wildfires from all land areas in the Arctic (66.6°N–90°N; left) and sub-Arctic (60°N–66.6°N; right), from 2003 to 2022. The colours indicate the total monthly emissions in June (orange), July (blue), August (green) and in all other months combined (yellow). Data: CAMS GFAS v1.2 wildfire data. Credit: CAMS/C3S/ECMWF.

Annual total estimated carbon emissions (megatonnes) from wildfires from all land areas in the Arctic (66.6°N–90°N; left) and sub-Arctic (60°N–66.6°N; right), from 2003 to 2022. The colours indicate the total monthly emissions in June (orange), July (blue), August (green) and in all other months combined (yellow). Data: CAMS GFAS v1.2 wildfire data. Credit: CAMS/C3S/ECMWF.

Speaking to CNN, Robert H Holzworth, a professor of Earth and Space Sciences at the University of Washington, said, “Thunderstorms occur when there is differential surface heating, so an updraft-downdraft convection can occur… You need a warm moist updraft to get a thunderstorm started, and that is more likely to occur over ice free land than land covered with ice.”

Soaring temperatures have also slowed down the polar jet stream — responsible for circulating air between the mid- and northern latitudes — due to less of a temperature difference between the Arctic and lower latitudes. As a result, the polar jet stream often gets “stuck” in one place, bringing unseasonably warm weather to the region. It also blocks out low-pressure systems, which bring clouds and rainfall, possibly leading to intense heatwaves, which can cause more wildfires.

All three factors — rising temperatures, more frequent lightning and heatwaves — will most likely worsen in the coming years, thereby causing more wildfires in the Arctic. By 2050, it is estimated that wildfires in the Arctic and around the world could increase by one-third, according to a report by the World Wild Fund.

How Arctic wildfires can exacerbate global warming?

When wildfires ignite, they burn vegetation and organic matter, releasing the heat trapping greenhouse gases (GHGs) such as carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere. That is why the rising frequency of wildfires around the globe is a matter of concern as they contribute to climate change.

However, in the case of Arctic wildfires, such GHG emissions are not the biggest worry. It is rather the carbon stored underneath the region’s permafrost — any ground that stays frozen for at least two years straight. Scientists estimate that Arctic permafrost holds around 1,700 billion metric tons of carbon, including methane and CO2. That’s roughly 51 times the amount of carbon the world released as fossil fuel emissions in 2019.

Wildfires make permafrost more vulnerable to thawing as they destroy upper insulating layers of vegetation and soil. This can cause ancient organic materials such as dead animals and plants to decompose and release carbon into the atmosphere. In case a large-scale thawing of Arctic permafrost is triggered, it would be impossible to stop the release of carbon.

This would mean that the world will not be able to limit global warming within the 1.5 degree Celsius threshold. Breaching the limit will result in catastrophic and irreversible consequences for the planet.

“What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay there — Arctic change amplifies risks globally for all of us. These fires are a warning cry for urgent action,” Mark Parrington, Senior Scientist at the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service, said in a statement last week.

To make matters worse, as of now, no one is keeping a tab on post-fire permafrost emissions, and they are not even fed into climate models. Therefore, there is no way to estimate their contribution to climate change.