Sports

Why this could be the most consequential election in college sports history

WASHINGTON — In September of 2020, during a contentious presidential debate and amid the COVID-19 pandemic, college football found itself at the center of the political sphere.

Then-President Donald Trump announced to millions watching on television that he “brought back” Big Ten football, claiming that he convinced league executives to play the sport after they initially wanted to delay the season to the spring. Big Ten university presidents and athletic directors soon afterward made clear that the conference decided to play fall football on medical advice and the increased availability of testing — not political influences.

No matter, the claims suddenly thrust the sport into a hotly contested presidential election.

Four years later, another divisive election arrives. And while the act of playing football isn’t in question, the act of paying football players is.

Tuesday’s elections — congressional races as well as the White House — loom as the most consequential in the history of college athletics, experts contend.

“Collegiate athletic policies — like so many issues — are hanging in the balance of the Tuesday elections,” says Julie Sommer, executive director of the Drake Group, an organization whose mission is to defend academic integrity within college athletics.

The elections coincide, ironically enough, with the initial release of the College Football Playoff selection committee’s rankings. While the top 25 has its own impacts, Tuesday’s other polls will be much more lasting.

Results could shape the direction of college sports during a pivotal time of transformation in the industry. As major college athletics moves closer to a professionalized entity, federal policy looms larger than ever for college sports decision-makers on at least three fronts: (1) comprehensive congressional college sports legislation; (2) the interpretation and enforcement of Title IX as it relates to athlete revenue sharing; and (3) the debate over college athletes as employees.

“There hasn’t been a time I can recall where every part of the college sports ecosystem, particularly the traditional powerbrokers, have more on the line in the courts and in Congress,” says Jesse McCollum, a longtime lobbyist working on behalf of The Collective Association, a group of NIL collectives.

Legislation

The leaders of college athletics — mostly NCAA executives and power conference administrators — have spent five years visiting Capitol Hill, all in an effort to encourage lawmakers to pass a congressional bill granting them protections to enforce their rules, many of which the courts and state lawmakers deem to be unfair.

In their most recent lobbying efforts, the conferences are requesting that any bill (1) prohibits college athletes from becoming employees and (2) codifies the NCAA’s settlement of the House antitrust lawsuit, which would likely entail the granting of a limited antitrust exemption.

Five years and millions of dollars spent, the lobbying efforts have produced one bill that advanced through a committee. That bill has not been taken up by lawmakers on the floor of the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives — a stalemate explained through disagreements between Democrats and Republicans on concepts of a college sports bill, all taking place against the backdrop of a split Congress (for now, the House is controlled by Republicans; the Senate by Democrats).

Control of the chambers is paramount to both a bill’s passage and its contents. Is the bill broad or limited, pro-NCAA or athlete-skewed? Sommer, an attorney and expert on these issues, sums up each party’s contrasting approach in this way: Republicans want to limit employment status and give protection to the NCAA and power leagues to grant them oversight and regulation; Democrats emphasize more rights of athletes, express an openness (some of them) to employee protections as well as health, educational access and gender equity rights.

Over the last three years, a group of bipartisan U.S. senators have championed efforts for a college sports bill, nearly arriving at a deal in May of 2021. In their latest efforts, Republican Sens. Ted Cruz and Jerry Moran and Democratic Sens. Richard Blumenthal and Cory Booker were engrossed in dialogue — until election season ramped up over the summer.

Cruz, in a tight re-election race with Democrat and former Baylor linebacker Colin Allred, is the “bellwether,” says Tom McMillen, a former U.S. congressman who’s lobbied on behalf of a college sports bill for years now. If Cruz wins re-election and the Republicans win enough races to take control of the Senate — polling shows this is probable — Cruz would become chair of a key committee that controls college sports legislation (senate commerce).

Cruz has publicly said he will make college sports legislation a “very, very high priority.” But even if legislation leaves the committee, it must be bipartisan in nature to get the approval of a full U.S. Senate. The election results are not expected to give either party a significant amount of control either way to get legislation through along party lines only.

And then, it must pass the House, which could flip, some contend, from Republican-controlled to Democrat. A divided Congress could present more problems.

“If Republicans take the Senate and Democrats take the House, it’s going to be difficult to get stuff done,” McMillen says. “If Republicans have a clean sweep, they could get all the agenda done. The more likely scenario is a split government and it’s going to require hard work to get a compromise done. I don’t see a clean sweep.”

Title IX

As part of the House settlement, schools will be permitted starting in July to share at least $20.5 million annually with their athletes. The initial cap figure for the 2025-26 academic year was distributed in a memo to power conference schools last week.

The interpretation and enforcement of Title IX in the new era of athlete revenue sharing is perhaps one of the more overshadowed and important matters within the college sports industry. Title IX is the federal law requiring educational institutions to offer equal opportunities and benefits to men and women athletes.

The U.S. president has significant influence over the direction of the Office of Civil Rights, the U.S. Department of Education office responsible for preventing discrimination in education. The president is charged with both making appointments of leadership positions as well as directing leaders within the department.

Experts believe that a victory from Vice President Kamala Harris — attempting to be the first woman president of color — will result in a more serious approach to the enforcement of Title IX as it relates to the distribution of revenue to athletes.

“That’s going to be a big factor,” says McMillen. “She would be taking office right when this whole [House] thing happens. I’ve talked to a lot of Democratic members. [The distribution method] is not sitting well with a lot of female members of Congress.”

What is the distribution method? There’s not one. Schools are permitted to distribute House-related revenue how they see fit. However, most plan to distribute the money unequally to their athletes, using the House settlement back-damage formula for the distribution: 90% to football and men’s basketball.

Sommer believes a Harris administration would be more “sympathetic to the historical and ongoing discriminations women athletes face” and that she would see the need for Title IX enforcement “in a revenue share distribution under current and future rules.”

Employment

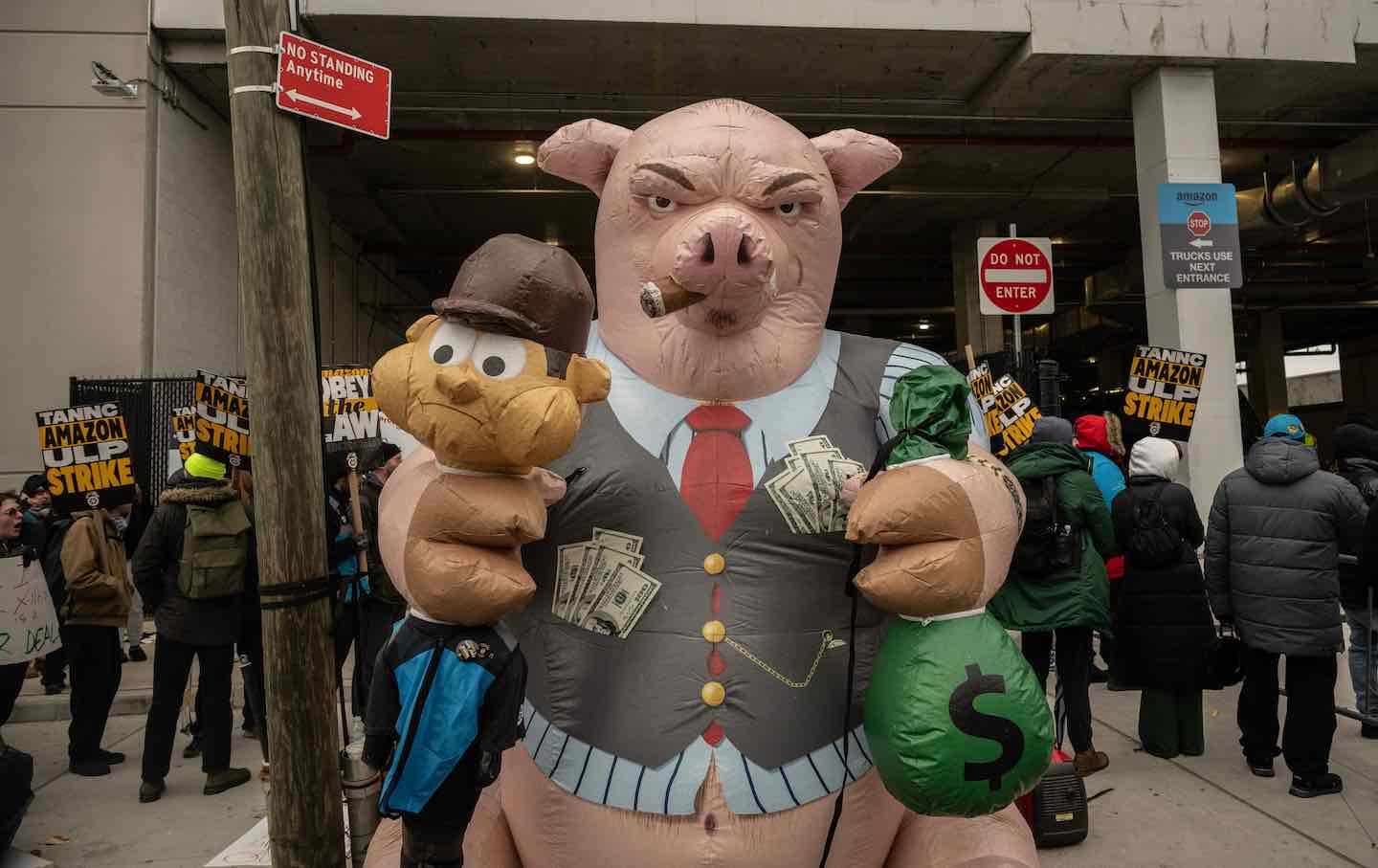

The endeavor to have college athletes deemed employees is a years-long movement that has divided college sports stakeholders.

A growing group of administrators and even coaches now believe employment is a path to stability and the regulation of an unwieldy system. Leaders of athletes rights groups, such as Ramogi Huma of the National College Players Association, have led the employment movement now for years.

Meanwhile, NCAA officials and many power conference administrators have strongly pushed against employment. And even some Democratic lawmakers have publicly acknowledged that employment for college athletes is not the right path.

Where does this end up? It may hinge on the election results, says Jim Cavale, the founder of a college sports players association named Athletes.Org. “The first way the election can impact college sports is whether or not athletes are employees,” he said.

For now, two routes exist for athletes to become employees: through the courts (there is already an ongoing case in Pennsylvania, Johnson v. NCAA); or through a tribunal such as the National Labor Relations Board, an independent agency that enforces U.S. labor law as it relates to collective bargaining.

The NLRB is actively pursuing unfair labor practices against USC and UCLA, as well as Dartmouth. The NLRB’s general counsel, Jennifer Abruzzo, is a presidential appointee who has been open about her support for employment of college athletes. The five members of the NLRB national board — key decision-makers in unfair labor practice charges — are also presidential appointees with term limits.

Under Harris, the general counsel and board would be expected to remain as is — a left-leaning group that supports employment — but a Trump administration is likely to entail a vastly different approach.

“The NLRB board matters,” Cavale said. “We’ve seen who’s president has a lot to do with what that board looks like. If Trump wins, [the employment movement] slows down. If Kamala wins, it speeds up.”

A change in control of the White House — from Democrat to Republican — would have a “huge impact” on the employment debate, said Michael LeRoy, an Illinois law professor who has published extensive work on labor policy.

“Trump would immediately flip the general counsel,” LeRoy said.

There is something else too, says LeRoy. Trump has publicly suggested he would eliminate the Department of Education, a decision that could have serious ramifications on university funding.

“Since the 1880s, universities have been funding things like college football — building stadiums and such — and when you take out the academic funding at at time when the House settlement is imposing cost on these schools, something has got to give,” LeRoy said.

“We would be in a world of unprecedented chaos. College athletics could not avoid the fallout.”