World

World Humanities Report, directed by UC Berkeley’s Sara Guyer, warns of extinction risk to human knowledge – Berkeley News

What role do the humanities play in a world challenged by climate change, rising authoritarianism, censorship, racism, wars and collapsed economies?

The humanities and their forms of historical, visual and cultural literacy are critical to understanding and addressing the human experience and the planet’s survival, says Sara Guyer, dean of the Division of Arts and Humanities in UC Berkeley’s College of Letters and Science.

She should know: Guyer is director of the prestigious World Humanities Report, a major international study organized by the Consortium for Humanities Centers and Institutes and commissioned by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Council of Philosophy and the Human Sciences. The report is complete today (Monday, Oct. 14) with the publication of her final director’s report.

“We live in a world and planet under duress. We are wanting for tools and concepts that foster change and help us live under these shared, if still uneven conditions,” Guyer writes in her report, which accompanies and summarizes the larger report, “… the humanities are of critical importance to that future.”

The World Humanities Report is the product of 230 scholars and writers whose documentation of the contributions and condition of the humanities in their parts of the world culminated in 115 essays, reports and case studies. It also includes 10 recommendations for how university, government, philanthropic, policy and other leaders can protect the humanities and prevent their extinction.

The strategies include investing in humanities research, protecting freedom of inquiry as a right, and preserving archives, languages and language study.

In the following Q&A for Berkeley News with Sarah Fullerton, Guyer talks about the state of the humanities in different parts of the world, the conditions under which they persist, the risks to their disappearance and their “liberatory power.“

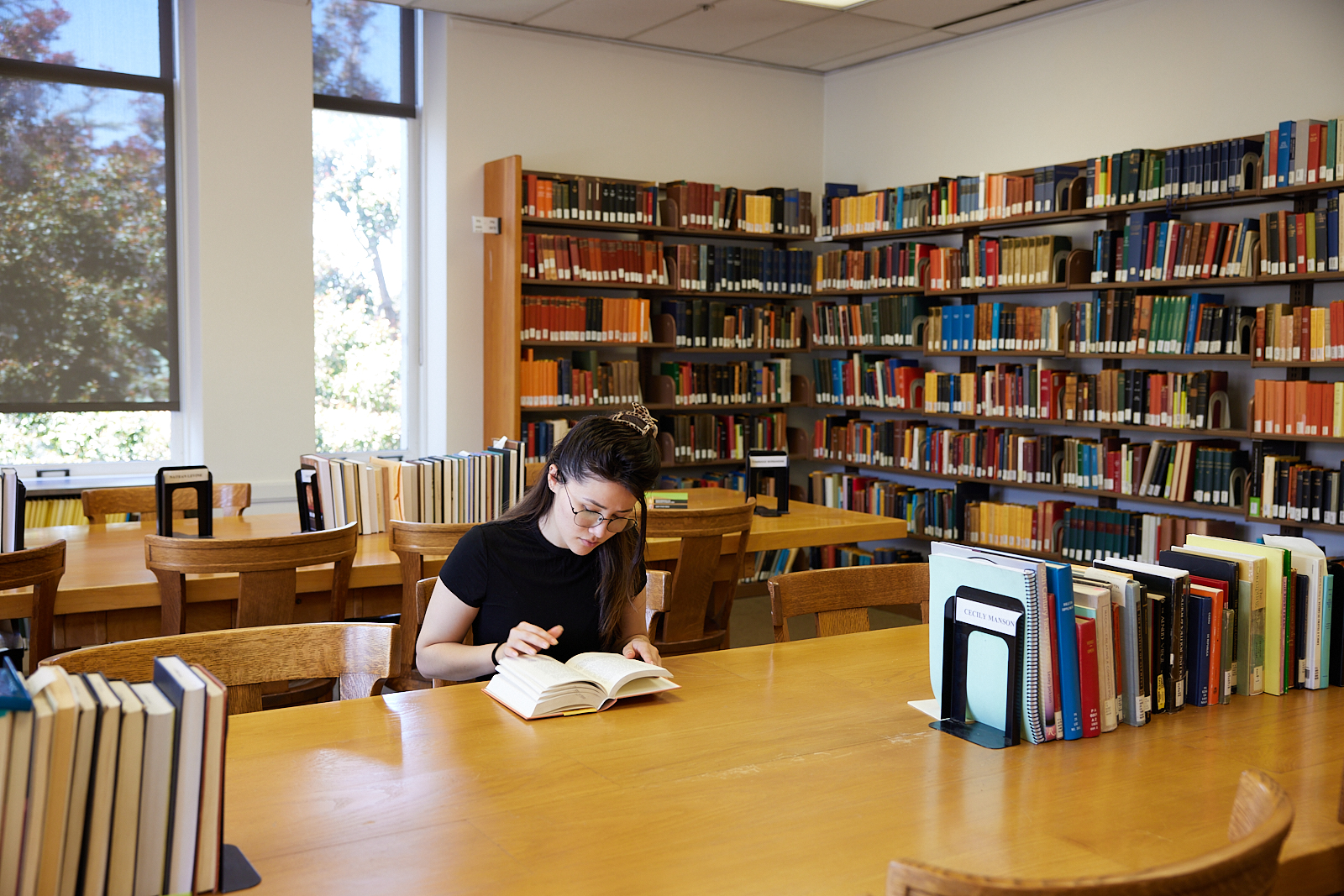

Grant Kerber/UC Berkeley

Sarah Fullerton: The 2024 World Humanities Report was six years in the making. Why is it important, and how is it produced?

Sara Guyer: I should start by saying it wasn’t supposed to be the 2024 World Humanities Report, and it wasn’t supposed to take six years. Originally, it was planned as the 2020 World Humanities Report. We started the project in 2018, but the pandemic significantly delayed us.

We had plans to meet in person over a series of months, but soon after our second meeting, in Germany, the world began to shut down. While we moved to Zoom, we were working across so many time zones and so much uncertainty.

The goal of the report is to demonstrate the vitality of humanities research around the world – both inside and adjacent to universities – and to establish a set of policy recommendations to ensure that the humanities persist. Over the past decade, there have been other humanities reports commissioned by institutions or states, including the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Those tended to be smaller in scope and relied on literature reviews, bibliometrics and surveys.

… today, the humanities are threatened for the very reasons they are powerful. They challenge conventional narratives and offer alternative — or what some have called more accurate — histories and imaginaries.

Sara Guyer, dean of the Division of Arts and Humanities

We wanted a more expansive, representative and grassroots approach, where the questions came from nine different regional research groups that defined the humanities locally. We asked them to describe trends, risks and new methods. We asked them to give us a window into their collaborations, institutions and funding structures.

The rigorous documentation of research practices around the world, represented in the report, is also a kind of advocacy. Take, for example, the Arab Region: No state or institution in the region could gather this information in a reliable way and make it publicly available. Seteney Shami, who led the research in the area, makes this point, and I want to emphasize that, as a world monitor, we were able to reflect the conditions in universities in ways that are verifiable and trusted.

In many parts of the world, this information is not just unreliable, but buried, so that the humanities appear not to exist. One explanation is that what U.S. universities call “the humanities”— the study of literature, philosophy, aesthetics, ancient and modern cultures and history — is not distinguished in these other contexts from the social sciences or “human sciences” or, in some cases, the professions.

Jen Siska/UC Berkeley

As a result, without our on-the-ground accounting, it is difficult to know much about how institutions recognize or support the humanities, as they are bundled with so many other fields of study.

The most substantial regional account of academic disciplines appears in the contribution from China, which provides, for an international audience, a striking overview of how humanities research is structured within Chinese universities, in particular tensions between classical and critical (or western) approaches.

Similarly, the report from Russia details how the critical humanities have been forced out of Russian universities and how the effect has been to isolate Russian scholars from the rest of the world.

Jen Siska/UC Berkeley

Technology has contributed to many of the world’s challenges, such as artificial intelligence and climate change. But in your director’s report, you say that solutions to issues like these are deeply humanistic. How so?

Many of the challenges we face today are brought about by technology, whether climate change and the production of carbon or rapid developments in artificial intelligence or even elements of misinformation and anti-democratic movements.

While we actually know a great deal about the climate crisis and its causes, understanding how we respond to it and how we understand it involves more than science. Ethics are part of the story, but the humanities go beyond ethics to reveal how we imagine the future and our relationship to mortality, risk, agency and loss, both as individuals and as a species.

Today, we need more than new policies, which are, of course, important. The humanities offer a vast archive of literature and philosophy that helps us understand how humans have thought about about the future. Similarly, the humanities have a significant role to play in shaping the future of AI. Philosophers and humanists are already working alongside — even inside — tech companies.

So this isn’t a moment of crisis, but of risk. If we don’t recognize the importance of the humanities and continue to support them, we could face a real crisis.

Sara Guyer

Are the humanities in crisis, like many critics assert?

The answer is yes and no. Let’s start with no. We were really deliberate in deciding that this was not going to be an account of crisis, and that wasn’t difficult: Everywhere we looked, we discovered scholars and students working on new knowledge. Sometimes this was in universities and at other times at the periphery, whether in publishing houses and journals, NGOs or museums. We also wanted to focus on the conditions of flourishing, now and for the future.

That said, today the humanities are threatened for the very reasons they are powerful. They challenge conventional narratives and offer alternative — or what some have called more accurate — histories and imaginaries. We see this in the U.S. around the history of slavery and civil rights, and it’s true globally. If the humanities weren’t important, they wouldn’t be so contested. The very power of the humanities to reveal unsettling truths makes them vulnerable to repression.

So this isn’t a moment of crisis, but of risk. If we don’t recognize the importance of the humanities and continue to support them, we could face a real crisis. Supporting the humanities requires ensuring academic freedom, preserving archives and fostering a broad array of research, from traditional scholarly work to new strategies, like community collaborations and documentary filmmaking. We need to reinvest not just financially, but also culturally and politically. If we only focus on producing solutions, building a workforce and professional schools, we do risk losing the humanities.

One of the really important insights of the World Humanities Report is the observation made by James Shulman, of the American Council of Learned Societies, that the greatest funding source for humanities research is undergraduate students. There is no graduate student or faculty pipeline — and hence no research pipeline — for the humanities without undergraduates in our classrooms and universities.

Jen Siska/UC Berkeley

One of the most essential ways that we support humanities research is by hiring ladder-rank faculty and supporting robust graduate programs. Those graduate programs, in turn, depend on there being faculty positions available when Ph.Ds finish their degrees. But if undergraduate enrollments decline and the academic job market shrinks, that entire pipeline for humanities research will collapse. What does this mean? It means that fundamental research into human expression and experience, past and present, actually depends on our students — the future of knowledge is in their hands, and we should not take that lightly.

So one key thing we can do at Berkeley, within the UC system, nationally and internationally, is to ensure that high schools, communities and the media recognize the humanities as valuable to society. Students in California and around the world, particularly those who seek economic mobility, need more than narrow professional tracks; we need to acknowledge that the humanities open up worlds — whether they’re career paths or intellectual experiences. And this is important not only for individual students, but also for the very future of knowledge — and the university — itself.

At Berkeley, we are making sure students find their way into humanities classes, especially after a long period when these pathways were blocked — whether due to advising, the negative media representations of the humanities, or the way that high schools and admissions officers presented the humanities as weak alternatives to vocational fields.

Jen Siska/UC Berkeley

There are inequalities worldwide in knowledge, access and representation. Is Berkeley taking action to improve access?

Definitely. One powerful example at Berkeley is the work that global art history Professor Anneka Lensen and others are doing with Syrian filmmakers and artisans — some of which is coming to the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive — reflecting an important collaboration between the Division of Arts and Humanities and the museum.

There are also opportunities coming through the Consortium of Humanities Centers and Institutes, based at the Townsend Center for the Humanities, which is fostering research collaborations with universities in Chile, South Africa, Kenya, India and elsewhere.

In the division, we’re also addressing ongoing gaps in access to knowledge through faculty hiring. The African Humanities Initiative is a clear example. Across departments we’ve worked with over the past three years to deepen the study of African literature, history, music and art with new faculty in the history of art, English, comparative literature, Middle East languages and cultures, and hopefully in the coming years in French, music, and film and media, among others. This is a transformation and is opening up immediate opportunities for students. One of the most vivid is Professor Zama Nsele’s trip to the international art fair in Dak’art, which was an opportunity she made available to students.

Jen Siska/UC Berkeley

Why is funding the humanities — one of the report’s recommendations — especially urgent today?

The humanities — globally, but also within U.S. universities — have become more vulnerable as a result of state and private disinvestment. Over the course of this century, funders have shifted their focus from open inquiry to solutions-based knowledge and grand challenges. The risk here is that when new funders enter the space left open by the abandonment of the humanities and recognize that the humanities are actually enormously valuable — both because they represent cultural capital and because they have the power to reframe history and reveal unsettling truths — we risk a loss of freedom.

We already have seen international humanities research and advocacy organizations become dependent on shadowy funders for their survival. What will happen if the newest supporters of the humanities are authoritarian actors?

We already have seen the repression of artists and scholars all over the world, and without institutional or state funding from the U.S. and Europe, we should be on guard for increased reliance of humanities organizations on anti-democratic actors. This is a major shift and a new form of global dependence. We need funders in democratic states to think about institutional sustainability and reinvest in universities so that they can remain sites of open inquiry.

That’s why the recommendations in the report are so urgent.