World

World’s oldest cave painting now dates back 51,200 years

It’s unclear when ancient humans first arrived on the shores of Sulawesi, a 71,898-square-mile Indonesian island west of Borneo. The oldest-known skeleton dates back to between 16,000 and 25,000 years ago, while some stone tools and rock shelters seem to have been assembled more than 118,000 years ago. Fossil bits from long-gone megafauna, whose quantity and concentration suggest they were hunted to extinction, indicate that other hominin species may have colonized the island earlier still: at a maximum of 194,000 years ago when Indonesia was still connected to the rest of Asia via a land bridge.

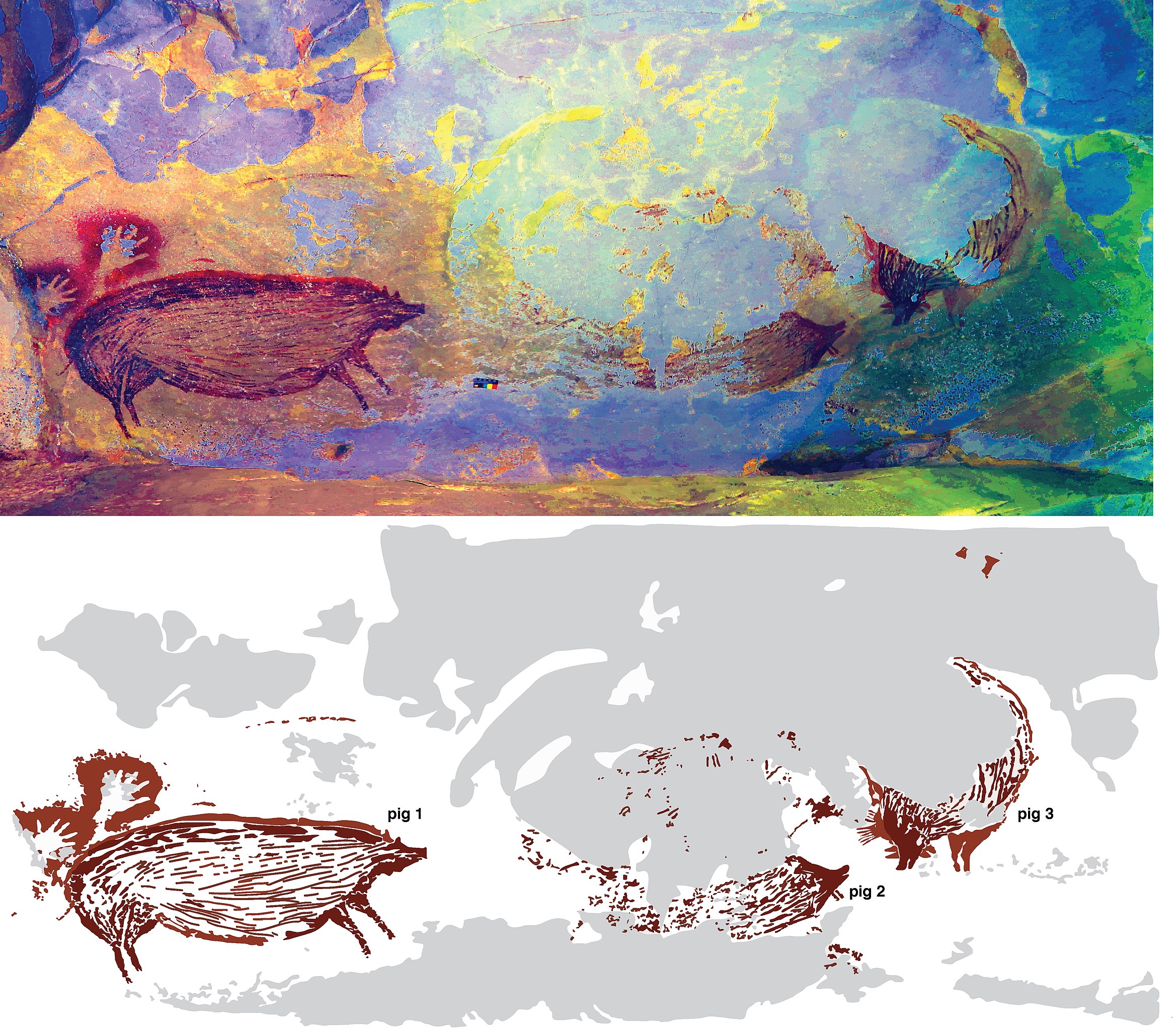

Equally puzzling is the origin of the island’s vast collection of cave paintings. The oldest among them — a 14-foot-wide panel of spear-wielding stick figures surrounding what archaeologists describe as warty pigs and “dwarf bovines” — was initially dated to 45,500 years ago, making it not just the oldest in Asia, but one of the oldest in the entire world.

A recent study published in Nature has raised the age of this prehistoric work of art to a minimum of 51,200 years, further challenging our understanding of when and where humans first evolved the capacity to create figurative images.

How to date a cave painting

Found in 2017 at an archaeological site called Leang Karampuang, located near the island’s southernmost tip, the pig and bovine painting was dated the same way all cave art is dated: by measuring the decay of uranium atoms in the rock layer ancient artists used as their canvas. Until recently, this was done by physically excavating bits of rock and placing them underneath a spectrometer to detect the level of uranium decay.

The technique, though tried and tested, has its drawbacks. To avoid damaging the cave art, researchers can only extract the smallest of samples. On top of this, samples often contain not only the original rock wall but also other, younger layers of sediment deposited after the cave paintings were created, which archaeologists refer to as “cave popcorn.” Taking the average of both new and old layers alike, physical sampling tends to yield conservative but not necessarily accurate minimum and maximum ages.

The recent study used a new measuring technique called laser ablation, which uses lasers to scan rock walls without taking physical samples. In addition to being faster, cheaper, and less destructive, this technique allows researchers to tell the layers of sediment apart and only measure those relevant to determining the age of the cave paintings.

While layers of younger sediment “would be impossible to avoid when microexcavating,” the researchers noted that with laser ablation “these areas of localized digenesis [popcorn] can easily be avoided (that is, not integrated) when calculating [Uranium]-series ages from map data.”

Although laser ablation produces a larger margin of error than physical sampling due to smaller sample sizes, the authors — led by Indonesian archaeologist Adhi Augus Oktaviana — said that it leads to older and therefore more accurate minimum age estimates. This makes the technique a valuable asset in studying cave paintings like the one discovered in Leang Karampuang, which has been poorly preserved and covered with mineral-rich popcorn deposited after the artwork was created. If popcorn’s inclusion in the physical samples led to a conservative estimate of 45,500 years, laser ablation confidently raised the painting’s minimum age to 51,200 — a difference as big as the time separating the present day from the dawn of civilization in Mesopotamia.

The origins of art

The conclusion presented by Oktaviana’s team challenges our notion of when and where the capacity to create art evolved. “Presently,” the authors noted, “the earliest widely accepted evidence for image-making by our species is from the Middle Stone Age [c. 100 to 75,000 years ago], and comprises geometric motifs.”

While archeologists previously speculated that figurative images — images that represent objects and tell stories — emerged in Europe during the Late Pleistocene, the newly dated paintings at Sulawesi suggest that they emerged before ancient humans migrated into Asia between 50 and 70,000 years ago. Experts like Chris Stringer, a British anthropologist working with the Natural History Museum in London, recently told the BBC that Oktaviana’s study provides reason to believe that the emergence of figurative art may even have predated human migration from Africa itself. (Ancient art has been discovered in Africa, though it was not figurative art.)

But that’s if these drawings of warty pigs and dwarf bovines were indeed created by ancient humans. While measuring uranium can help us figure out how old a painting is, it unfortunately does not tell us anything about the hands that made it. Considering Sulawesi was populated by other hominin species before the arrival of Homo sapiens, it’s possible that these paintings were actually the work of our extinct relatives. The oldest known cave painting in the world, located at Maltravieso cave in Spain and thought to have been created around 66,700 years ago by Neanderthals, is but a series of hand imprints. Either other species of hominin were capable of creating figurative art — something for which we have yet to find definitive evidence — or we ourselves learned to make figurative art much, much earlier than previously thought.

This question is by no means trivial, as the emergence of figurative art not only played a crucial role in the evolution of our cognitive abilities, but also in the development of civilization, allowing our ancestors to record and easily communicate ideas, emotions, and social conventions.

As Oktaviana and co-authors explained in the study:

“In contrast to single-figure depictions, the agency of the juxtaposed figures constituting a narrative scene allows a story to be told through images in a manner that does not require the producer of the art to be present to convey the narrative to an audience. Scene-making has therefore been linked to an increase in the potential for images that persisted on rock surfaces to transmit particular narratives (such as myths) over long periods of time, especially when combined with oral traditions.”

While the origin of figurative art remains riddled with questions, using laser ablation on other cave art in Europe, Asia, and Africa can potentially point us to answers in the future.